Michel de Montaigne urged Western culture to think and talk more about death, but Western culture still hasn’t listened

In his three-volume collection of Essays (1580), the French thinker Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) famously declared that the best way to prepare for death was to think about it constantly. “Let us have nothing so much in minde as death. At the stumbling of a horse, at the fall of a stone, at the least prick with a pinne, let us presently ruminate and say with our selves, what if it were death it selfe?” Montaigne advised that we must contemplate death at every turn and in doing so, we make ourselves ready for it in the most productive way possible. On a more personal note, I managed to achieve this by spending four years writing a Ph.D. thesis on Montaigne’s work, a task which forced me to contemplate death every single day.

Arguably every Ph.D. dissertation carries with it a certain amount of doom and gloom at some point or other, especially during the last few months of writing up. But studying time in Montaigne’s work meant being constantly steeped in his musings and recollections on how ancient philosophers viewed suicide, or the history of funeral practices in Western Europe. By the time I had finished, I was sure Montaigne was wrong, and that in fact I should never think about death again. The stress and anxiety surrounding my submission date meant that the words of a 16th century nobleman concerning the nature of death were low on my list of priorities. And yet on reflection, thanks to Montaigne and his open and honest approach to mortality, thinking about death has actually taught me a lot about how to live.

Thanks to Montaigne and his open and honest approach to mortality, thinking about death has actually taught me a lot about how to live.

Despite what many of us may think in today’s society, talking about death on a regular basis doesn’t have to be scary or morbid. In fact, it can actually make us feel a much deeper connection to the natural world that simultaneously puts the little things into perspective. After all, mortality is a key feature of pretty much everything that exists in Nature, human beings included. The sun, stars, plants and animals — nothing lasts forever, and Montaigne constantly argues in his writing that this is most evident in the mutable physical processes that occur around us: “The world runnes all on wheeles. All things therein moove without intermission.” Winter storms and snows give way to summer sun, flowers wilt and perish. Even the Sun will disappear one day. As humans we fit perfectly into this cycle; we regularly define our lives in terms of birth, aging and death. Montaigne describes his own aging body using seasonal imagery: “I have seene the leaves, the blossomes, and the fruit; and now see the drooping and withering of it [his body].” However, in the natural world, death always gives way to new life. Leaves fall from trees and die before the arrival of new shoots that burst forth in the spring. When human beings die, their bodies decompose and mingle with the Earth, or sail along the breeze as specks of dust, ready to become part of something else.

Thinking about death in this way really helped me to understand that our lives are only one small piece of a much bigger picture — and the bigger picture doesn’t care about how many Twitter followers a person has, or how much money they earn, or where they buy their clothes. It’s easier to put trivial things to one side when we think about how our death actually confirms a meaningful, physical connection to the world around us — we are natural beings who arguably exist for a certain length of time before returning back to the Earth in some form or another. If you’re a fan of The Sopranos, this attitude is perhaps best summed up by the old Ojibwe saying that Tony finds in his hospital room — “Sometimes I go about in pity for myself, and all the while a great wind carries me across the sky.” The end of our life doesn’t mean the end of Nature’s great cycle. As Montaigne remarks, we can find comfort in the fact that our death is merely one part of a much greater plan: “your death is but a peece of the worlds order, and but a parcell of the worlds life.” His tone is so self-assured in the expression of these ideas that his writing becomes living proof of our ability to master any fear we might have about death. Instead we can allow ourselves to return to Nature.

And yet, talking and writing about death constantly is an approach towards our own mortality that often seems completely alien to modern Western cultures. (Eastern cultures are way ahead and can be looked to as an example.) Nowadays it’s relatively rare to engage in an open conversation with friends or family about how we want to be buried, or what happens to the soul after we die. Often these discussions are relegated to funerals or college philosophy tutorials, or they simply don’t happen at all. But Montaigne states time and again that such avoidance is unhealthy and impractical; instead he declares “let us have nothing so much in minde as death” and regularly draws on ancient philosophy to back up his ideas on confronting death head-on. For example, he uses the Stoic philosophy of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (26 AD — 180 AD) to argue that we should relish spending our leisure time in contemplating the meaning of death. Like Montaigne, I believe it is possible to gain a huge degree of contentment from life through attempting to understand death. As well as feeling closer to Nature, death encourages a greater awareness and enjoyment of the present moment. In a strange way, acknowledging that death is certain actually allows us to adopt a more practical attitude towards the time that we do have on Earth. In her book Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer, Barbara Ehrenreich encourages us to appreciate life “as a brief opportunity to observe and interact with the living, ever-surprising world around us.” Personally, I’ve found myself feeling extremely grateful during times that I have experienced intense happiness, as well as reaching an understanding during periods of sadness that — like everything else — this too shall pass.

By way of contrast, the death-defying attitude of Silicon Valley in recent years provides an interesting case study in 21st-century conversations about mortality. Rather than acknowledging death, a growing number of tech giants are now actively trying to eradicate it. Social commentators argue that modern society is sometimes guilty of believing in its own immutability, as though certain scientific and technological advances give human beings an absolute right to live on forever. Indeed, the cycle of Nature that I described at the beginning of this essay is currently being overturned in order to make way for advances in 3D organ printing, nanobots that can replicate immune systems and even blood injections that supposedly extend our lives. Peter Thiel, one of the co-founders of PayPal, has admitted that he is ‘against’ the idea of death and aims to fight it rather than accept it. The National Academy of Medicine is currently running a “Grand Challenge in Healthy Longevity” which will award $25,000,000 to anyone who can make a major scientific breakthrough in delaying the aging process. Many of the project’s investors want aging to be stopped completely. Meanwhile, Google’s highly secretive Immortality Project was launched in 2014 and aims to treat aging as a disease that can be cured.

There is a distinct air of confidence surrounding these endeavors; for many tech giants it is not a matter of if immortality can be achieved, it is simply a matter of when. Speaking to Tad Friend of The New Yorker, Arram Sabeti of the food tech start-up ZeroCrater once stated, “The proposition that we can live forever is obvious. It doesn’t violate the laws of physics, so we will achieve it.” The “we” in this context is questionable, since many of these projects are being supported by tech giants and celebrities who will undoubtedly be the only people able to afford an immortality cure if it ever becomes available in the future. These advances are being energetically pursued by people who head up large corporations with arguably little thought or respect for death itself, only the right to continue existing. This isn’t accepting death or preparing for it, this is trying to abolish it in the unhealthiest way possible — surrounded by secrecy, with little thought for the long-term effects on society. Such measures do nothing to cure fear of death, they only try to stop it at all costs, which is really just a form of denial.

What would the author of the Essais have made of these developments? Montaigne was famously suspicious of doctors during a time when modern medicine simply didn’t exist. He often complained that doctors were desecrating the natural duration of the human body and interfering with what he considered to be Nature’s work. Even in an age before painkillers or anesthesia, Montaigne (who famously suffered from excruciating kidney stones) was proud of his ability to withstand illnesses and diseases ‘naturally’: “We are subject to grow aged, to become weake and to fall sicke in spight of all medicine.” Therefore it’s very hard to describe the horror Montaigne would have felt upon being confronted with the idea of death-defying technological advancements such as nanobots and 3D organ printing. Not only are these inventions a human attempt to subvert death by artificial means, they also pose other problems too. For millennia, one of the most positive aspects of death originally proposed by Stoic philosophy (and later adopted by thinkers such as Montaigne) was the idea that death comes for everyone. In other words, it doesn’t care about social class — the rich human being dies just like the poor human being and thus reminds us that deep down we are all equals. Will that be true in the future as well or not? Cryogenic preservation is becoming more and more popular, but it currently costs as much as $200,000 to freeze the entire body. We have to imagine that a drug or injection to cure mortality will be ten times as costly. This means that immortality will most likely be for the few, not the many.

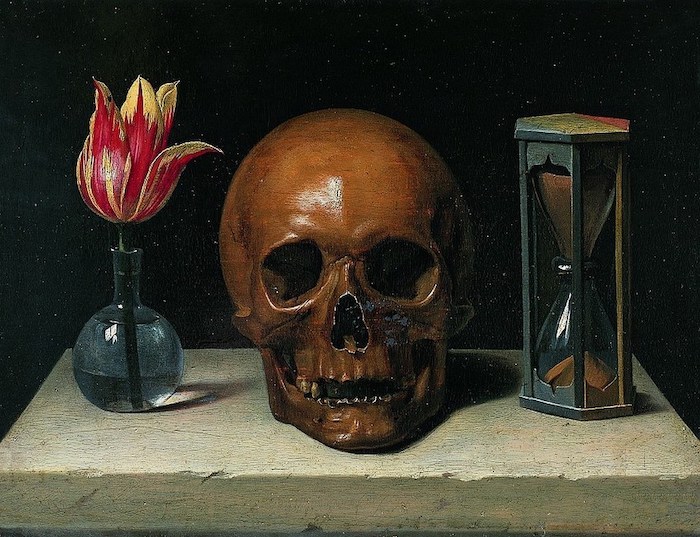

So what can we as human beings do to respond to death in a practical and healthy manner? Alongside the popular take-up of meditation and mindfulness (which psychologists have already noted can greatly improve our attitude towards death), a younger generation of advocates — most notably Caitlin Doughty — are heading up an increasingly popular “death-positive” movement. This trend encourages an enquiring approach towards death and funerary practices that draws on the type of calm, reasoned manner that Montaigne would have been proud of. Doughty’s website, The Order of the Good Death, states that the death-positive movement believes that “the culture of silence surrounding death should be broken through discussion, gathering art, innovation and scholarship.” This mission resounds with the philosophy of Seneca the Younger (4 BC — 65 AD), a thinker Montaigne turned to repeatedly when he wanted to understand fear of death. Seneca believed that approaching death through contemplation, mindfulness and discussion was one of the key virtues of wisdom; pursuing such an open and honest attitude towards death would eventually allow an individual to patiently wait for death, as one of nature’s operations. Therefore talking about death, studying philosophy, meditating, and even creating or appreciating art around this theme are all excellent ways to prepare for life’s end.

Talking about death, studying philosophy, meditating, and even creating or appreciating art around this theme are all excellent ways to prepare for life’s end.

We can also make sure to engage in practical preparations surrounding our funeral arrangements, wills and life insurance. Rather than becoming a depressing chore, instead we can appreciate that it brings peace of mind to family and friends, as well as ourselves. If we’re lucky enough to be dying in a bed somewhere, surrounded by loved ones, at least we can rest assured that these same people have been taken care of. In the Essays Montaigne praises the practical act of constructing your own grave — many of his friends prepared elaborate tombs, sometimes with their own death masks attached. Montaigne says that looking on a replica of your own dead face is an excellent way to prepare for the inevitable reality of the future and also shows you have taken the time to leave the world in an organized way. Incidentally, this is just one example which demonstrates that in the past, Europeans were far more attentive to the idea of preparing for death in a practical manner. Admittedly this may have something to do with the fact that death was far more visible in everyday life thanks to mass graves and public executions, not to mention the high rates of mortality, particularly amongst infants. Thankfully all of these things are in the past, but death still lingers in society, it’s just slightly more hidden away than it used to be. Whilst we can’t all afford a good death mask, it would be comforting to see a resurgence in openly discussing or enacting any kind of practical preparation for death, an attitude which has clearly been written out of European society in the last few hundred years.

In the Essays, death is natural. It forces us to realize our humble place in the great cycle of mutability that constitutes the workings of Nature. In the meantime, talking, writing and thinking about death can radically improve our quality of life by helping us to gain a greater enjoyment out of our time as one of the living, as well as helping those people we will eventually leave behind. I don’t want to start investing in cryogenics or constructing my own coffin just yet, but talking about death from time to time? That’s something we can all start doing right now.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!