By Ryland JAMES

It’s a task of grave importance, but there’s nothing to stop New Zealanders having a laugh as they work on DIY caskets in the country’s “coffin clubs”.

Elderly club members meet for cups of tea, a bit of banter, and to literally put the final nail in one-of-a-kind coffins that will carry them to their eternal resting place.

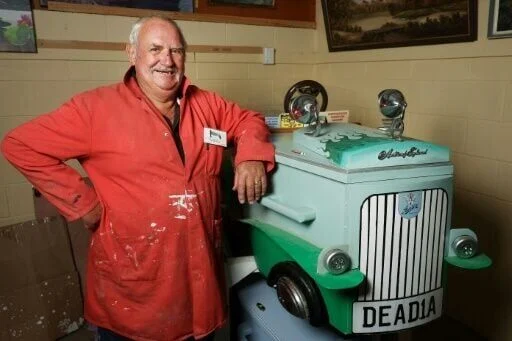

Kevin Heyward plans to be sent off in a box resembling a vintage Austin Healey.

Registration plate: DEAD1A.

“My daughter came up with the idea,” the 79-year-old car enthusiast said with a grin, brushing sawdust off his overalls.

It’s fully equipped with a mock steering wheel, windscreen, rubber wheels with metal hub caps, wooden mudguards, a bonnet, painted-on side doors, and wing mirrors.

“The trickiest part was getting the mudguards lined up because of their curve,” Heyward told AFP at the workshop of the Hawke’s Bay Coffin Club in Hastings.

The hefty casket, which can be carried with six wooden handles, even has working headlights. The batteries, naturally, are currently dead.

“It weighs quite a bit and I’m a big man,” he said.

“I have said to my six grandsons they had better start weight-training, because they will be carrying it one day,” Heyward chuckled.

“There is a bit of humour in this car.”

The club is one of four that have sprung up around New Zealand, with the first opening in 2010 in Rotorua on the country’s North Island.

Some clubs boast as many as 800 people on their books, though one admitted “not all of them are above ground”.

At the Hastings club, Jim Thorne, a spritely 75-year-old motorcycle fan, used his skills as a cabinet maker to build a casket painted with a motorbike track. It’s stored in his garage, alongside a collection of motorbikes.

Thorne said most friends “are a little aghast and say ‘why are you doing that?'” when they hear about his coffin-making hobby.

“Apart from the fact that I like the look of mine, it’s my input into my final days.”

– ‘Dying to get a coffin?’ –

“There is a certain mindset in some people that this is almost a taboo subject that they find very, very difficult to talk about,” Thorne said.

“They tend to overcome it. At the end of the day, it’s a reality of life, unfortunately.”

He breaks the ice with newcomers by asking: “Are you dying to get a coffin?”

But the club’s atmosphere is far from morbid.

Banter flows during the morning tea break as members chat over scones and hot drinks.

“We’re a bit unique, but we are happy. There are always lots of jokes,” said club secretary Helen Bromley.

Most members are seniors. The club provides a space to open up about death and dying during weekly meetups.

“I think everybody here has accepted that they are going to die, whether they’re decorating their coffin or helping others with theirs,” Bromley said.

“We’re a club that tries to empower people to plan their coffin, to plan what happens if they get sick.”

She said some members want to spare relatives the burden of meeting rising funeral costs. The club will also build and decorate coffins for grieving families.

On average, a funeral in New Zealand costs around NZ$10,000 (US$6,200), according to the national funeral directors association.

Coffin prices range from NZ$1,200 to NZ$4,000.

– ‘Remember Me’ –

For a NZ$30 membership, the Hastings club gives each new member a pressed-wood coffin in one of three designs, ready to be decorated.

The coffins come in four sizes, each costing around NZ$700, extra for paint and a cloth lining.

During a tea break, Bromley announced that a member suffering from cancer was in intensive care after a fall. Her brother had asked the club to finish her coffin as a priority.

The club also builds ash boxes, which they sell to the local crematorium, and small coffins for infants, which they give away.

“The midwives and nurses at Hastings hospital have asked us to not ever, ever stop making the little coffins for them,” Bromley said.

“We donate to whoever. If there’s a miscarriage at home and they want a coffin, we donate.”

Members help knit blankets, teddy bears, pillows and hearts to go in the infants’ coffins.

Committee member Christina Ellison, 75, lost an infant daughter in 1968 and said she was comforted to know the club helps other families grieving the loss of a child.

“The little baby coffins are so beautiful and done with so much care. The knitting that the ladies do is incredible,” she said.

Ellison is moving away soon and plans to take her coffin, which has been painted a blue-grey colour called “Remember Me”.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!