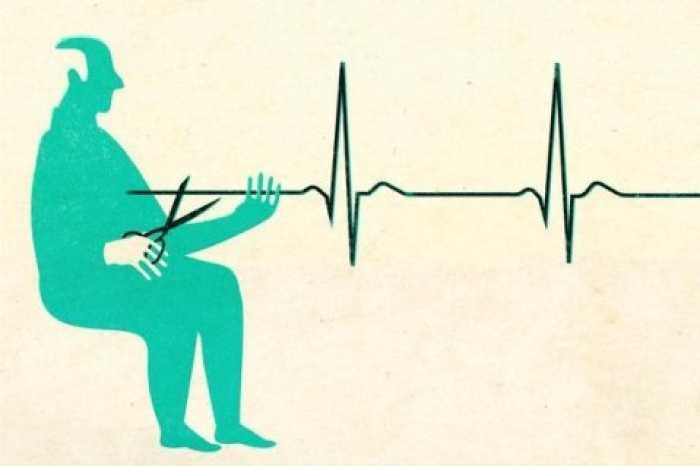

Terminal restlessness is the term for a set of symptoms that can happen at the end of a person’s life. These symptoms can include agitation, emotional distress, and confusion.

These symptoms can sometimes be accompanied by more severe psychological symptoms, which are generally known as delirium.

Terminal restlessness can be caused by a number of things associated with dying, including the medications used to relieve symptoms, organ failure, and emotional distress.

Read on to learn how to recognize the symptoms of terminal restlessness and how to help someone you love cope with the physical, mental, and emotional experiences that may come at the end of life.

Terminal restlessness can look different in each person it affects. Some people can become much calmer than they usually are, while others might grow aggressive or have mood swings.

Common symptoms of terminal restlessness can include:

- confusion

- agitation

- anger

- emotional outbursts

- unusually calm behavior

- a lack of attention to surroundings

People with terminal restlessness may also demonstrate unusual behaviors. These behaviors often take place when the person is in an agitated state. Examples include:

- pulling on intravenous tubes (IVs)

- pulling off clothing

- pulling and tugging on bedsheets

- fighting with or insulting loved ones or caretakers

- making accusations based on events that might not have occurred

- searching or asking for items they don’t actually want

- rejecting physical touch and affection from family and other loved ones

People who are experiencing terminal restlessness can also experience delirium, which can cause extreme confusion along with other symptoms, such as:

- lack of awareness of surroundings

- limited short-term memory

- limited attention span

- disorientation

- delusions

- hallucinations

- sleep disturbances

- inability to regulate volume or speed of voice

- sped up or slowed down body movements

Terminal restlessness happens at the end of life and doesn’t necessarily have a specific cause.

The process of dying causes physical changes to the body and is often mentally and emotionally overwhelming. This can lead to terminal restlessness and delirium.

Some medications prescribed to help treat the pain and symptoms associated with certain medical conditions can also lead to restlessness and delirium.

Some of the most common causes of terminal restlessness include:

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy kills cancer cells, but it’s hard on the rest of the body and can lead to restlessness in people approaching the end of life.

- Pain medications: Opioids, steroids, and other pain medications are often prescribed to help reduce pain and give comfort during end-of-life care. But they can also increase the risk of delirium. This risk increases if someone is experiencing organ failure.

- Organ failure: Organ failure can make it impossible for the body to carry out basic functions. This can change how brain chemistry works and can lead to terminal restlessness and delirium.

- Pain: It can be difficult to manage pain effectively at the end of life. Severe pain that isn’t well controlled can increase the riskTrusted Source of terminal restlessness.

- Medical difficulties: It’s common to experience medical difficulties like anemia, infections, fevers, or dehydration at the end of life. These can all affect how the brain works and lead to terminal restlessness.

- Urinary retention and constipation: At the end of life, the muscles that control urination and bowel movements can weaken and fail to function properly. This can lead to constipation and urinary retention. Both can cause pain and lead to terminal restlessness.

- The emotions of dying: Dying carries a heavy emotional toll for everyone. It’s common to experience grief, stress, fear, and other strong emotions. This distress can lead to terminal restlessness.

The management of terminal restlessness and delirium depends on the person and their symptoms.

Some management options include:

- switching medications or doses of medications

- talking with someone who’s experienced in end-of-life care and counseling, such as hospice social workers or grief counselors

- consulting with spiritual leaders, such as priests, ministers, rabbis, or imams

Terminal restlessness or delirium can sometimes lead to behaviors that are harmful to the person or to others. In these cases, additional treatments like antipsychotic medications can ease agitation.

Doctors will discuss end-of-life treatment plans with family and caretakers, to make sure everyone understands the options.

End-of-life care includes caring for a person’s physical, mental, and emotional needs.

Services such as home healthcare or hospice can help family or caretakers provide the right care to their loved ones. Each person’s exact needs will differ — but some general tips for end-of-life care include:

- Look for ways to ensure your loved one isn’t in any pain:Speak to a doctor and medical team about prescriptions and about any signs of pain you notice.

- Keep tasks simple: It’s normal for people to feel tired during this time. Make tasks like going to the bathroom, eating, and other daily needs as simple and easy as possible.

- Provide blankets, fans, cool washcloths, and other ways to control the temperature:Look for signs that your loved one is too hot or too cold. They may not be able to easily express their discomfort, so check for hands and feet that are cool or hot to the touch, and pay attention if they’re repeatedly tugging on a blanket.

- Check for comfortable breathing: It’s common to have trouble breathing at the end of life. Raise the head of the bed, turn on a humidifier, or move into a position that makes breathing easier.

- Be aware that your loved one might stop eating: Help your loved one eat and speak to a doctor about medications that help with nausea and vomiting. Remember that as they get closer to death, it’s normal and OK for someone to simply stop eating.

- Keep skin moisturized with petroleum jelly and other alcohol-free lotions: Help protect your loved one’s skin by rolling them over in bed every couple of hours. This will keep them from laying on one side for too long and help prevent bedsores.

- Talk with your loved one about their emotions: Dying can be an overwhelming emotional experience. Being a supportive listener can be an incredible help. Ask if your loved one would like to speak to a professional, such as a counselor or social worker.

- Talk with your loved one’s care team if you notice any mood or behavior changes: It’s normal to have a lot of emotions about dying. But if your loved one seems especially depressed, anxious, or distressed, talk with their care team. Mental health professionals and medications can help.

- Offer opportunities to connect with faith:Spiritual practices are important to many people at the end of their life. It can help to have religious texts or music available. A visit from a religious leader can also bring comfort.

- Offer companionship: Simply not being alone can often make a big difference. Try spending time with your loved one by talking, watching favorite films, reminiscing, holding their hand, or listening to music.

- Continue to talk:People may be able to hear even after they stop responding. That’s why doctors often encourage caretakers, family members, and friends to have final conversations with people who are dying, even if those people can’t respond.

It can be difficult to watch a loved one while they’re dying, and terminal restlessness can be especially challenging and overwhelming.

That’s why it’s so important for the caregivers and family members of people who are experiencing terminal restlessness to seek support. It can help to:

- Turn to other family members: Often, even phone calls with friends can help take some of the weight off of your shoulders. Friends and family can also make meals, run errands, and take care of other tasks for you.

- Take a break: Make arrangements to take a walk, go to the gym, or do anything else that’s out of your home and on your own for an hour or so. This can help clear your head and relieve your stress.

- Look into respite care: If you need a longer break, respite care can be the answer. Respite care can help make sure your loved one is looked after for hours, days, or even months.

- Seek grief counseling: Grief counselors are professionals who can help you process your emotions. Your insurance company might cover this kind of counseling. If not, there are ways to find low cost services.

- Look into peer support or online group support:Peer and online support groups can help you connect with other people who are facing the same challenges as you.

- Consider hospice care: Hospice care can provide nursing, caretaking, medical, mental health, social work, and other services to terminally ill people. Hospice is often covered by Medicaid, and most hospice providers also offer services such as grief counseling for family members.

- See if a nearby community center, nonprofit, or religious organization has resources: Many churches, senior centers, community nonprofits, and other organizations have outreach programs that can help provide hot meals, housekeeping, and other services while you care for your loved one.

It can be difficult for family members and caretakers to watch their loved ones experience the symptoms of terminal restlessness.

If you or a loved one is terminally ill, make sure to take the time to care for yourself. Grief counseling, peer counseling, and other supportive services can help make the end of life less overwhelming and help caretakers practice self-care and avoid burnout.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!