The family stops on a country road. Ted stands outside, listening to the wind as he often enjoys during the road trips. He turns around to look at his children and grandchildren, but they’re already in the car driving away. He’s alone.

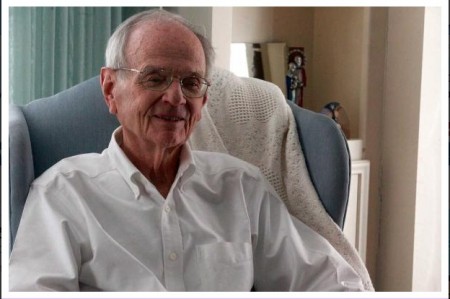

He rustles around and realizes it was a dream Still, it is the closest the 80-year-old Lubbock resident has ever been to fearing death.

Dotts fears becoming an ugly, grouchy old man when medication can’t alleviate his physical pain. But he doesn’t fear death.

He knows it’s inevitable.

He has known that ever since he was diagnosed with prostate and bone cancer in September — ever since he decided to opt against curative treatment for the crippling disease, refusing to put the burden of his health on taxpayers.

“My life — I’m richly happy, probably happier now than I’ve ever been, and that lasts through the day most of the time,” said Dotts, pastor emeritus of St. John’s United Methodist Church. “Death is a matter of releasing me from anything that’s less than God … and I get ushered into a new life and then I’m trusted to make whatever is to be made.”

Preparing for death

Two yellow folders are taped on a closet near the entryway of the Dottses’ home.

Betty’s folder is simple: An out-of-hospital “Do Not Resuscitate” order in case she dies at their apartment at the Carillon LifeCare Community in Lubbock.

Ted’s orders, written in all caps, are more detailed: No CPR. No hospital. No EMS-ambulance. No ER. No antibiotics. No tracheotomy. No breathing assistance devices.

While the doctor’s orders stop there, it’s followed by 12 phone numbers for Betty to call when her husband inevitably dies.

The couple has talked about death for years — not every day, but enough to understand each other’s end-of-life wishes. But after Ted’s cancer diagnosis, death became more imminent.

“(When I found out,) I had a feeling of the heart just sinking, like the bottom had dropped out,” Betty said. “But I also, in my thinking, knew ‘Alright, this is a time to prepare yourself.’ ”

She is not only preparing herself for the emotions that will surround the death of her husband, but the practicality of it.

Without Ted’s help, Betty will be completely alone in running their household, including finances that Ted manages online.

“I don’t like computers, so I’m learning about the computer,” Betty said. “He’s very careful with all our money and how it goes and where it goes to and so forth, so he’s teaching me.”

When a person maps out different scenarios for his death and decides what he’d like to do in each situation, it lifts a burden from any family who may be stressed out about what to do following a terminal diagnosis, said Charley Wasson, executive director and CEO of Hospice of Lubbock.

He said it also takes away second-guessing and allows families to make end-of-life decisions confidently instead of out of fear.

As Betty takes care of her husband during his illness, Ted knows she’s already suffering the grief of losing him.

Ted also experiences grief in not being able to take care of Betty when it’s her time to die.

“I’ll be gone and who will be that close to her? Children, of course, but they have their own lives,” Ted said. “You can hire doctors and nurses, but it won’t be anyone that close to her as she is to me. … That’s a loss that I have and every day I have to see her and know that she’ll have to go through much of this death by herself and won’t have me there to do what she does for me.”

Making the decision

The shots would cost $5,000.

It was too much.

Ted knew the treatment would be covered by Medicare. But, he already had his rules in place, including not using community resources to prolong his life for only a couple of months when he had already exceeded the life expectancy for the average American male.

After the cancer diagnosis, the doctor told him about the recommended treatment, including radiation, surgery and, of course, the shots.

“After you’re 80 years old, some studies show you’ll spend more on the last six months of your life then you spent your first 80 years of your life,” Dotts said. “Some of those expenses are extremely high.”

Created in 1965, Medicare was intended to answer growing reports of impoverished seniors languishing or dying because they lacked health insurance.

According to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, more than 50 million seniors and nearly 3 million Texans are enrolled in the government program. Even though Medicare spending is trending down by nearly $1,200 per beneficiary, overall spending grew 3.4 percent to $585.7 billion in 2013, or 20 percent of the nation’s total health expenditures.

Dotts doesn’t want any part in it.

Instead of spending Medicare funds on prolonging his already fulfilling life, Dotts said he would rather those funds be available for his 18-year-old grandchild or 40-year-old child.

That’s one of the main reasons that outside of pain medication, Dotts isn’t taking anything to treat the cancer.

“I’ve known Ted for years and so he had a very thoughtful, long progression of thought. He’s held this standard that this is how he’s going to die: He’s not going to use community resources and he is going to utilize hospice for years,” Wasson said. “That’s not only a gift to himself but a gift to his family and the people around him. He’s very comfortable in that decision.”

Wasson said he agrees with Ted’s decision to focus on quality of life rather than prolonging it.

“If many people had the opportunity to talk to Ted and his rationale about why he made that decision many years ago, why he’s held true to that decision for many years, I think a lot of people would see wisdom in it,” Wasson said. “But I don’t think a lot of people get to because they don’t have the conversation.”

Ted and Betty moved to the Carillon LifeCare Community seven years ago, knowing they’re at the other spectrum of life.

Although Betty said Americans may be living longer, there’s still a responsibility to take care of future generations.

“It’s just not fair for our children and grandchildren, just because he could spend a lot of money (on cancer treatment) and Medicare would pay for it,” Betty said. “But somebody is paying for that and money is going to be taken from here to give to there and he said, ‘I do not want to take the community resources from others just so I could live a few more months.’ ”

Dealing with the pain

Betty imagines her husband falling to the floor as he’s walking up the stairs to their apartment. Other times she pictures him stumbling and pretending to faint. Betty knows it’s not real; they’re simply imagining for the inevitable.

“There’s so much involved. It’s a major event in life to die and we try to get through it without talking about it, but then all of a sudden you’ll be faced with it,” Ted said. “We get to share that and the rich depth of (imagining death). I thought we were pretty close but we’ve gotten closer than I ever dreamed now that death is next door.”

Although he hasn’t broken any bones yet, Ted’s pain varies on a daily basis. Eventually it was bad enough that he received a shot that doctors assured him was not for longevity, but rather to help alleviate the severe pain.

“They warned him the pain is going to get worse for two weeks and then it will drop, and so on a scale of 1 to 10 he got at least to a 7 and maybe higher,” Betty said. “You can’t sleep when you have that kind of pain, but then it did drop after two weeks and it’s gone down. … Many people live with pain and it’s learning to manage the pain. It’s not that he doesn’t feel it, but it’s where it doesn’t dominate him.”

Despite the pain Ted endures, Betty said she wasn’t surprised by her husband’s decision to receive palliative care rather than curative treatment.

“His personality is one in which he thinks things through and reasons things through, tries to see both sides and to see the larger picture. He does not just jump into something, knee-jerk,” Betty said. “Most mornings he will be studying for several hours and he studies not just the Bible or theology, but psychology or history and certainly death.”

Lasting legacy

By helping residents with paperwork for food stamps, the Dottses still connect with the community around them despite living in a retirement home. They know their pain will end soon and that it doesn’t compare to the suffering others endure daily.

Ted hosts local radio show “Faith Matters” but has contributed to the community in the past as a longtime clergyman and his work as former senior vice president of ethics and faith for the Covenant Health System.

The Dottses also started the first Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays in Lubbock in 1993.

“We started the PFLAG and that was overshadowed with fear and anxiety of persecution or vandalism or maliciousness. I don’t think that’s near as possible now, plus you have gay marriage that has passed in several states so I think it’s a movement that’s thriving and flourishing and helping people care for each other,” Ted said. “I go to sleep at night, and Betty does too, very grateful that we got involved. … People who have same-sex love and they’re persecuted over it, it can make them mean and bitter but for the most part.”

And through panel discussions at churches around Lubbock, Dotts has also shared his end-of-life decision with the community, once again bringing to the forefront a topic that may be difficult for some people to face.

Wasson said he hopes Ted’s openness inspires residents to talk about end-of-life decisions and discuss at what point it becomes about quality of life, rather than treatment to add a few months or years of battling an illness.

“In America we are a death-averse society. We don’t like to talk about death, which is why Ted’s talk the other night was so special, because he was very honest and open about death and his journey,” Wasson said. “I think this is quintessential Ted. He is great at bringing people together and talking about the tough in life and doing it with a great amount of grace and eloquence.”

Accepting death

Ted doesn’t know if he has two months left to live, or two years. But, the couple’s faith puts them at ease.

“I don’t think God even notices whether we’re dead or alive,” Betty said. “It doesn’t matter that much; we are still loved by God whether we’re here or there, and what there is, we don’t know, we haven’t been there. But, it’s our faith and that trust (that) we’re going to be cared for and loved and it’s going to be alright. It’s going to be good so I don’t have to get all uptight (about dying).”

They do have their moments of grief, but the couple mostly laughs and teases one other.

They realize this time next year, Ted may be dead, but the talks about his death have brought them closer.

“It’s like being able to see into each other’s heart and to be right with them,” said Betty, who will turn 79 in a few weeks. “He kept saying he wanted to live longer so he could take care of me when I died, but he’s dying first.”

Complete Article HERE!