— And when it may help

By Dr. Rachel L. Ombres AHN

Caring for people with serious illnesses or chronic conditions is one of health care’s most complicated — and important — challenges.

While medicine continues to improve the way we treat diseases such as cancer or heart failure, it doesn’t always do a great job of caring for the things that matter most to patients and their families, such as physical and emotional distress.

And despite their frequent visits to doctors and hospitals, people living with serious medical conditions may still have unaddressed symptoms like pain or fatigue, and often report poor communication about those symptoms with their health care providers.

In other words, medicine is pretty great at treating the disease — but not as good at caring for the whole person.

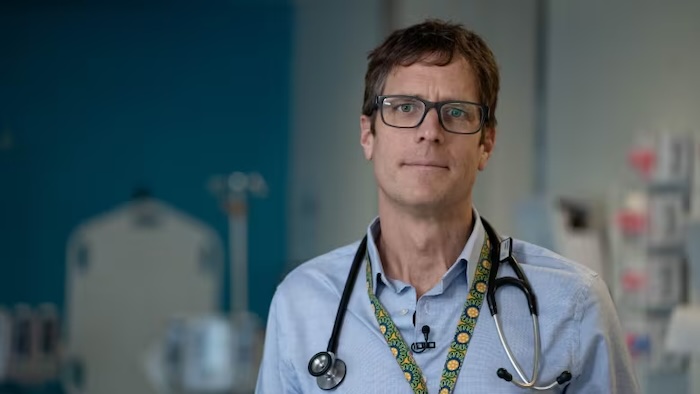

That’s where palliative care specialists enter the picture, helping people live and feel better throughout the course of a serious illness.

Palliative care is a growing field of medicine that focuses on helping patients and their families cope with the physical and emotional stressors of advancing health problems. There is strong evidence that palliative care not only can improve quality of life for seriously ill patients, but also may reduce avoidable hospital admissions and enable patients to spend more time at home doing what matters most to them.

What is palliative care?

Palliative care focuses on providing people with relief from the symptoms and stressors of serious illnesses, such as cancer, chronic heart or lung disease, dementia, neurologic diseases like Parkinson’s, chronic liver disease, kidney failure, and many others.

Delivered by a specialty-trained team of doctors, nurses, social workers and other clinicians, palliative care provides expertise in symptom management, care coordination and communication, with the goal of improving quality of life for both the patient and their loved ones. Palliative care is appropriate for people at any age, and any stage of a serious illness.

Importantly, palliative care is not the same thing as hospice.

While palliative care is led by clinicians specifically trained in that field, it’s provided in collaboration with other health care providers, including primary care doctors and specialists — and, unlike hospice care, it can be administered at the same time that the patient is receiving curative treatment, and at any stage of serious illness from the time of initial diagnosis.

A person with cancer undergoing chemotherapy, for example, might benefit from palliative care, as would a person with lung disease seeking a lung transplant. In fact, when people facing a serious illness receive palliative care early in their disease and alongside treatment for their underlying condition, evidence demonstrates that it may even prolong survival.

Unfortunately, the historical misunderstanding about palliative care’s association with hospice — and the general lack of awareness about palliative medicine as a specialty, even among providers — means that millions of people who could benefit from palliative care don’t get it.

Worldwide, only about 14% of people who need palliative care currently receive it, according to the World Health Organization.

Where can I receive palliative care?

Palliative care is provided in all settings. To best meet the needs of their patients, palliative care teams see people in the hospital, outpatient clinics, nursing facilities — and even in the comfort of their own homes.

Providing home and community-based palliative care is not only convenient for patients and their families, but it also aims to reduce certain complications of advanced illness that would otherwise require emergency room visits and hospitalizations.

The benefits — patients who feel better, have fewer unnecessary hospitalizations and have more support during stressful times — are attractive to patients, families and insurers alike. As a result, insurance providers such as Medicare are changing the way they reimburse for home-based palliative services, while health systems and other agencies are actively expanding access to palliative care across Pennsylvania and nationwide.

Today, there are more options than ever for home- and community-based palliative care.

How palliative care can help: One patient’s story

Barbara had just retired from a career in management at a local grocery store. She looked forward to the added time retirement would give her to do what mattered most, like spend time with her family and tend to her garden.

Unfortunately, a new cancer diagnosis thwarted these plans, and she was soon spending more time in the chemotherapy suite than with her grandchildren or her prized perennials. Barbara’s pain and fatigue prevented her from being active outside and limited her appetite.

When her primary care provider referred her to palliative care, Barbara was unsure what to expect.

The palliative physician suggested several interventions to help Barbara feel and function better, including medication changes and gentle exercise techniques, and provided additional resources for her family. The palliative care team also helped Barbara understand her care options and encouraged her to speak up about her preferences to her other health care providers and to her loved ones, so that everyone was on the same page about supporting her goals.

In time, these interventions helped lessen Barbara’s symptoms and streamline her care. Throughout her cancer journey, the palliative care team has remained a constant layer of support for Barbara and her family. With close attention to her goals and symptoms, the palliative care team helps Barbara live as well as possible, despite having a serious illness.

If you or a loved one has a serious medical condition, ask your doctor or insurance provider about a referral to palliative care.