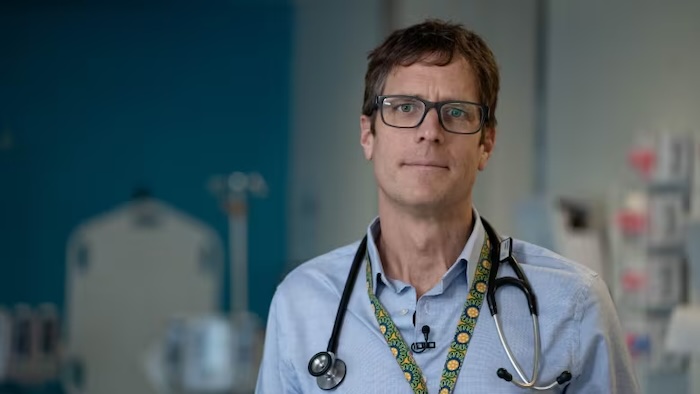

— Doctors including Zachary Tait and Rupal Shah, and recently bereaved readers Jo Fisher and Rebecca Howling, respond to Adrian Chiles’s column on how his father spent two of the last days of his life alone and distressed in A&E, for no good reason

My condolences to Adrian Chiles on the death of his father. His column describing the futility of his father’s last “precautionary” trip to A&E (3 April) highlights a rising challenge of the ageing population. As health and social care services collapse, the harms and indignities of hospital admission increase, especially for those least able to advocate for themselves. As a junior doctor working in A&E, I loathed watching frail, mostly older people languish on trolleys in corridors, receiving substandard treatment that they didn’t want and were unlikely to benefit from. This is now the norm in every hospital I’ve been to.

A 2014 study showed that more than a quarter of hospital inpatients die within a year. The risk, perhaps unsurprisingly, increases with age. It is our responsibility as clinicians to have difficult and frank conversations with patients ahead of time; to be pragmatic, realistic and kind in our decision-making. Unfortunately, lots of this comes under “planning for the future”, which tends to slip down the to-do list during a crisis. It is the single most rewarding part of my work to have the time and opportunity to make care plans with patients, to know what matters most to them, and to stop the “shrugs” that Chiles faced at every turn. But medicine-by-protocol is quicker and cheaper than thought and pragmatism, so as resources are stretched ever further, it may continue to flourish. I am so sad for Peter Chiles’s distress, and so grateful that his son uses his voice to call attention to it.

Zachary Tait

Manchester

I have been a GP partner in Battersea, London, for 20 years. Unfortunately, Adrian Chiles’s opinion piece absolutely resonates. As clinicians, we are now taught to prioritise “safety” over all other considerations – despite the dangers inherent in doing so. Really, we are often protecting ourselves more than we are protecting our patients – an inadvertent side-effect of our unforgiving regulatory system.

We doctors are behaving as “artificial persons” who represent the healthcare system, and not as moral agents who have a duty to create meaning with our patients. We urgently need to move into a moral era of medicine – one that rejects both the protectionism of the past and the reductionism of the current context, which so often results in the cruelties and inefficiencies that Chiles describes.

Rupal Shah

Co-author, Fighting for the Soul of General Practice – The Algorithm Will See You Now

Adrian Chiles’s article stirred my thinking, as I have been on a similar journey. My husband died two weeks ago, having been advised that he had three months to live. This proved to be the case. With the Hospice at Home service, the NHS was truly wonderful. He died, however, with morphine slowly killing him. This could have been prevented if an assisted dying law was in place. One of the nurses said that what we were doing was cruel.

We were able to resist a possible hospital admission for chest pains by having what is called a ReSPECT document signed by our GP for “do not resuscitate”, and because we had an advance directive, dated 2022, that had been placed with the GP and was on his medical records. This made the whole process so much easier for us, but also for the various wonderful medics. Parliament needs to update our laws to align with so many in this country who wish for greater clarity and support Dignity in Dying.

Jo Fisher

Brampton, Cambridgeshire

In response to Adrian Chiles’s article, and having recently lost my own father, the best advice I can offer anyone is to make sure you have power of attorney in place for your parents. That is the way you can ensure that you have the power to override the decisions of medical staff who, while acting with the best intentions, will not know your parents as well as you do and may not make the decision that is best for them, or what they would have wanted. Having a power of attorney in place is more important than a will, in my view, because it enables you to help your living parent and ensure that their wishes are complied with. In my father’s final days, I was asked numerous times: “Do you have power of attorney?” I was very relieved to be able to answer: “Yes.”

Rebecca Howling

Toft, Cambridgeshire

As the daughter of an elderly parent, I very much understand the need for A&E avoidance, to cause least distress. No doubt waiting haplessly alone for many hours hastens demise. However, as a GP, I know that the huge increase in litigation over the last 20 years is a very real threat to doctors’ livelihoods. Even a simple complaint from a patient or their family can cause weeks, months, sometimes years, of stress to a health professional. Ruminating over every decision, every action or inaction, every justification, is enough to give us a heart attack – or worse, to make us follow in the footsteps of Paul Sinha and Adam Kay and quit the profession for a more peaceful existence.

Name and address supplied

Dear Adrian, I am so sorry that this happened to your dad. Sadly, it is a story repeated again and again. I am what is termed a “late career” doctor (over 55), and I recently transitioned from working as an emergency consultant to become a GP working in aged care. Over my 30-year career, mainly in emergency and other hospital specialities, although including a significant period in palliative care, I slowly came to appreciate that the way we have set up our emergency system doesn’t serve older people at all, and the frailest elderly are generally so poorly served that transferring them almost inevitably makes things worse.

My residents (200 across five aged care facilities) all have discussion and documentation of whether they should go to hospital and under what circumstances. The staff know to call me if there is any uncertainty, day or night. I do lots of family meetings so relatives can feel confident that the right decisions will be made. I love looking after old people and ensuring they get the best care that is right for their individual circumstances.

I firmly believe that aged care in particular is a GP subspecialty of its own. Too often care is fitted into lunch breaks and “on the way home” visits, and devolved to phone services out of hours. This is no way to treat our oldest and frailest, who deserve so much better. Again, I am so sorry.

Fiona Wallace

Sheffield, Tasmania, Australia

I read Adrian Chiles’s article about his father’s experience with empathy. My own father led a district health authority, with many hospitals under his care. He was intensely proud of the NHS, but in his 90s he was very clear that he didn’t wish to die in hospital or even to be admitted again unless absolutely essential. If he had an infection, he would be treated at home. Should it worsen and Dad die, it would be in his own bed. As a family, we listened. I was caring for him and know it took a huge weight off Dad’s mind to know that he need not dread the ambulance or the bewilderment of a strange place. Too many elderly people die in the back of ambulances and in A&E. Let those who are able to do so make informed choices about their end of life. It is a great comfort to them.

Dr Jane Lovell

Ashford, Kent

Adrian Chiles is correct that decisions about sending frail and elderly patients to hospital can be due to doctors being risk-averse. Doctors face a double jeopardy from the General Medical Council, who can take their livelihood, and the legal system if things go wrong.

Not all families can accept when beloved elderly relatives have reached the end of their life. Some people have unrealistic expectations about what healthcare can achieve in frail patients, and push for investigations and treatments even when it seems unlikely to affect the final outcome. If these are not performed, doctors can be accused of negligence or ageism. Most doctors would like less invasive healthcare at the end of life for themselves and their own families than they routinely offer to patients.

I would encourage everyone to write an advance directive or “living will” outlining how they would like to be treated in the event of their health deteriorating. I would also suggest giving a trusted person power of attorney for healthcare. These can be very helpful in reducing incidents like the one described in the article.

Dr Stephen Docherty

Consultant radiologist, Dundee

I would like to express my condolences to Adrian Chiles on the death of his father. I can empathise with him on many levels. I too lost my father recently in not dissimilar circumstances. I am a practising GP, a former medical director of an out-of-hours GP service, and now spend most of time as a management consultant trying to influence change in the NHS to stop incidents like this happening.

When I talk to clinicians and managers, I am always humbled by their devotion despite the pressures they work under. In my current assignment, over 32% of clinicians feel they are burnt out, and many more express intense frustration with the low-value clinical work they undertake. There is a limit to how much the system and the individuals who prop it up can give. The demand for care is rising every year.

I suspect that the GP who decided to send Adrian’s father to A&E without seeing him was under pressure to make a number of decisions that night. Given more choice, I’m sure they would have prioritised cases such as Adrian’s father over lower-priority, often unnecessary cases. What we do not discuss as a society with as much fervour as the system and those who provide care is how we consume care, so we can create time and space to support those who really need necessary attention.

Dr Riaz Jetha

London

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!