First and foremost: It’s okay not to be okay.

By Perri O. Blumberg

Along with what you’re going through individually, the world is going through collective grief: Amid the coronavirus pandemic, economic insecurity, and racial and political unrest, so many people are struggling to find hope. It’s hard to fathom the 562,000 lives (and counting) that we’ve lost in America alone from the pandemic. Hundreds of thousands of people are dealing with the loss of a loved one due to the virus.

On top of that, family members and loved ones are grappling with added layers of hardship and isolation the pandemic has created in the wake of a loved one’s passing, even if it’s not a COVID-19-related death. “Periods of grief following loss are notoriously isolating and difficult to navigate; grieving during a pandemic where many are socially distanced and unable to participate in traditional rituals of grieving, such as funerals and memorials, can make the process more complex,” says Courtney Bolton, PhD, a psychologist in Nashville, Tennessee.

And for the BIPOC community, it’s a particularly difficult time. “BIPOC communities have been disproportionately impacted by COVID deaths, and this reality is rooted in a long history of racial disparities within the healthcare system in the US,” says Pria Alpern, PhD, a psychologist in New York City who specializes in trauma and loss. Those inequities exist in mental healthcare too, which leaves BIPOC people in distress, less likely to gain access to the mental health services they need to process their grief, Alpern adds.

While navigating the death of a loved one is never easy, there are coping strategies out there that can help you through. Below, explore experts’ advice and steps you can take in dealing with loss.

How does loss affect you mentally and physically?

Can’t lie to you: It’s grueling, life-changing, and awful. “Losing a loved one triggers a grief response, which is a normal psychobiological response to loss. When someone is grieving, they may experience a combination of yearning, intense sadness, along with thoughts, memories, and images of the person who died,” shares Alpern.

Of course, grief is entirely individual, and just like no one reacts the same way emotionally, grief will physically manifest differently for everyone. But Alpern notes that common physiological symptoms of grief may include difficulty sleeping, fatigue, nausea, headaches, and decreased appetite.

What do the “stages of grief” mean and are they true for everyone?

You may have heard of the five stages of grief or the Kübler-Ross model, named after the Swiss American psychiatrist who formulated the theory. These stages consist of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Some psychologists and researchers also go by a seven-stage model, which also considers shock and guilt, and pain as part of the grieving process. If you’ve lost a loved one and don’t feel like you’ve hit all these stages, does that mean there’s something wrong with you? Not at all.

Again, grief looks different on everyone, and many experts actually steer people away from reading into this definition of grief too heavily. “It’s important that we don’t define the grieving process by these stages, but rather acknowledge that grief varies individual to individual,” says Helen Rogers Pridgen, MSW, LMSW, vice president of programs at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “Grief can be messy. It can be cyclical and linger around important life events, words not said, and memories of the one we lost. We must allow ourselves to feel whatever we feel.”

These stages of grief are often not linear, Bolton adds. You might experience denial and anger even long after you’ve reached a place of acceptance, or you may skip over certain stages altogether.

What are healthy ways to cope with grief?

Know that it’s okay not to be okay. If you are experiencing grief or loss, Dominique Pritchett, PsyD, LCSW, a therapist in Kenosha, Wisconsin, emphasizes that now is not the time to pretend that everything’s fine. “It’s okay not to have all the answers. And it’s okay to ask for help.”

Feel your feelings. We know, it sounds like your friendly meditation app coach, but it’s true. Sometimes, simply telling yourself “I feel sad,” acknowledging it, sitting with it, and observing your feelings and bodily sensations as they arise can help make you feel better.

In certain marginalized communities, being in touch with your emotions can prove especially difficult. “It’s important to keep in mind that based on the role you’re in, you may feel obligated to suppress these feelings because of stereotypes or un-empathetic environments,” says Pritchett. “For example, Black women are typically criticized for appearing angry and aggressive, whereas their white counterparts may be given more empathy and compassion.” Those feelings of anger and frustration can build up over time if they go unexpressed, she adds.

Focus on having a routine and making plans. “While initially, you may not want to do anything, after a couple of weeks of mourning, getting back into a daily routine helps reset our habits and helps our minds move forward,” says Bolton. Routines and goals can be useful when you’re mourning, to reintegrate back into your community and remind you of the meaning in your life, she says.

Don’t stop pursuing your hobbies. Bolton suggests filling your days with small, fleeting pleasures. That could be a hot bath, dinner with a friend, or something as simple as a good piece of chocolate. And whatever you enjoy doing on a regular basis, keep doing it. “Passions, or our hobbies, give us purpose and more fulfilling enjoyment. Both of these are excellent tools to combat the stressful feelings that may arise from loss,” Bolton says.

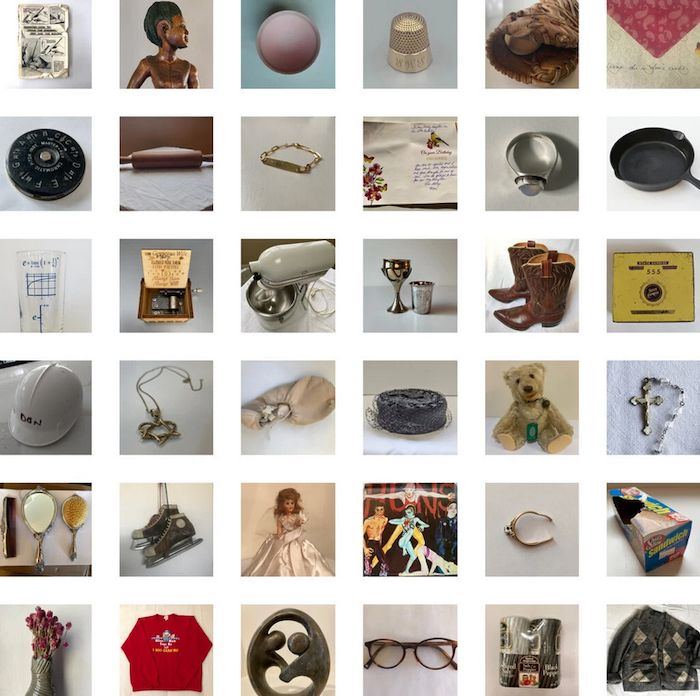

Honor your loved one’s life. Right now, this can feel challenging with the pandemic limiting in-person gatherings. But there’s still so much you can do. “It’s critical for many people to have a way to say goodbye or commemorate the passing of a loved one,” says Bolton. And currently, people might have to mourn in different ways, but “recalling positive memories and having the opportunity to share those with others helps us reimagine part of the mourning process that we enact in person at funerals,” adds Bolton.

She recommends creating some kind of keepsake about a loved one. That could mean putting together an album, a slideshow, or sharing pictures on a virtual site.

Trust in the passage of time. “Be patient with yourself and know that the process takes time, but the immediate pains will transform,” offers Bolton. “They may catch you by surprise down the road, and that’s okay. Be gentle and take care of yourself.” Time doesn’t heal all, but it can get you to a place where you may be able to look back on memories more fondly rather than being inundated with a surge of pain.

What can you say to someone who is experiencing the loss of a loved one?

It’s never easy to know how to comfort those who are grieving, whether it’s a relative, friend, or co-worker. Above all, sometimes just knowing you’re there for them can make a difference. “It’s important to validate, listen, and ask questions,” advises Alpern, cautioning people to avoid platitudes at all costs. Instead of saying things like “So sorry for your loss” or “That sucks,” try “I’m upset that this happened to you. What can I do to help?” or “It’s not fair that they’re gone. I don’t have words, but I’m here and listening,” she suggests. Or, a simple “How are you doing today?” a few weeks and months after a loved one’s death can really touch someone, too.

Alpern also recommends asking questions about the life and favorite memories of the person who died to create space for the grieving person to talk about the person they lost. It can feel uncomfortable but it supports the person grieving to create that space. “This is an important part of the grieving process. Be prepared to witness searing emotional pain and to sit with it,” says Alpern.

Even years after someone’s passing, on especially tough days, reaching out goes a long way. “Make note [to let someone know you’re thinking of them on] anniversaries of the passing, birthdays, or holidays, as these are often the most difficult times for individuals who are grieving,” Pritchett says.

Know that grief doesn’t just go away.

The experience of losing a loved one endures for a lifetime. Certain dates and even times of year will be hard annually, and even certain locations can be triggering. “The biggest misconception in our society is that grief goes away. Grief doesn’t go away, but it changes,” comments Alpern. “Over time, acute grief transforms and people integrate their grief in a way that allows them to continue living a fulfilling life.”

If you’re feeling consumed by grief and don’t feel you can continue with the routines of daily life, professional support, and in some cases, medication, can be key. “Seek out the support of a professional if you are struggling with your mental health. It can be comforting to share what you are experiencing with a trained professional,” says Rogers Pridgen.

In serious situations, you can also reach out to The Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741 or National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK, Rodgers Pridgen notes. There are also many grief support groups, so you may want to ask a friend for a local recommendation or consider a virtual bereavement group therapy platform, like Grouport and the Association for Mental Health and Wellness’ COVID-19 Bereavement Support Groups. The bottom line is that you’re not alone, and there are so many people grieving along with you—and resources out there to help you through it.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!