— Lessons from Victorian Mourning Culture

I needed others to see me—to acknowledge my grief.

By Kari Nixon

Reader, he died.

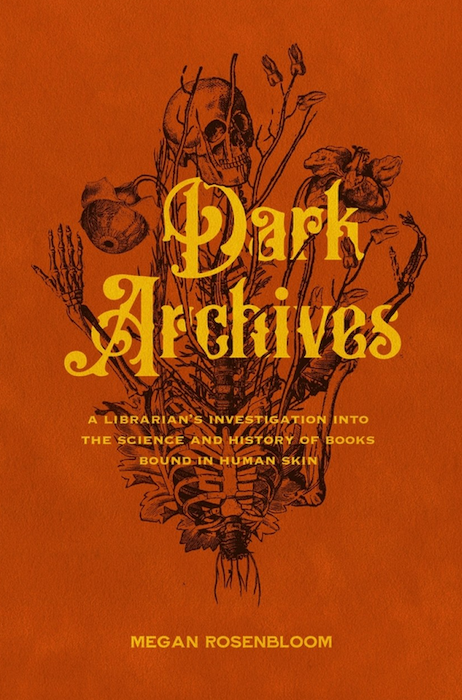

I’ve devoted my career to death. As a scholar of Victorian disease, I think about death nearly every day, but this did not protect me from the sucker punch of loss. Neither did his slow, prolonged decline, nor my slow, growing awareness of his coming end, like a roller coaster inching to the crest of a hurtling drop.

It hit me as I cradled my dog’s dead body: I was 32, a specialist in death, and I’d never seen a corpse before this moment. Even as my animalistic cries mingled with actual animal cries in the veterinarian’s office, the scholar in me awoke. How had I never seen a corpse? It struck me as I stroked his soft, velvet ears, no longer responsive to my love, that this separation from death—pervasive in modern society—is actually culturally and historically unprecedented.

Evidence of rituals associated with death is ancient—burials of modern humans date back about 30,000 years, a testament to the very human need for a physical means of coping with loss. Jewish communities sit shiva. At funerals, mourners also tear pieces of their clothing to mark the permanent rift left in the fabric of their lives. In Croatia, going into mourning is still standard. But in America and much of Western Europe, we’ve scrubbed society clean of anything that bespeaks death. We tend to see ourselves as beyond the pale of infectious disease, and we have developed an entire funeral industry to cart away death so we don’t have to see it. Yet, by privileging ourselves with this social sanitation that offers a fantasy of life free from death, we have, in fact, robbed ourselves of any means of coping with it.

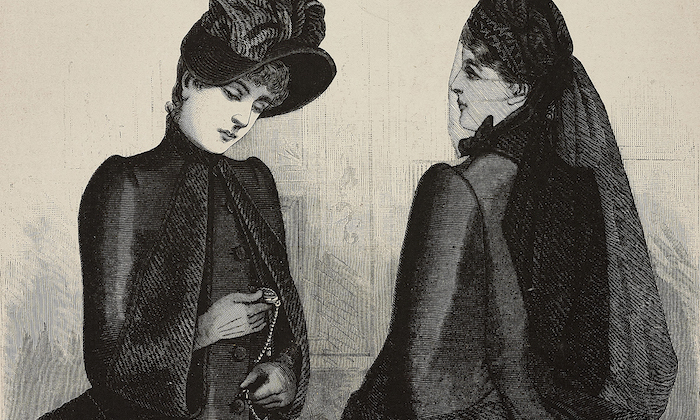

Caught in a vortex of loss, I felt profoundly the productive communal purpose of Victorian mourning culture. Victorian novelists often refer to mourning culture with wry disdain. I can appreciate their critique: After all, you were expected to go into mourning for your husband whether you were desperately in love with him or whether he was an abusive sadist. But in doing away with what can seem like fussy external markers of a deeply personal state, we’ve thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

Expected to teach my classes on Victorian culture and live my life with the stoic professionalism of the unbereaved, I felt lost after his death. I needed others to see me—to acknowledge my grief. Somehow that eased the nauseating feeling that my loss of something tangible was itself intangible. So, with the existential defiance of the bereft, I went into Victorian mourning. I wore black clothes and jet jewelry for weeks, comforted by their mute message: “Here stands loss … unalterable, unutterable loss.” In 2019, though, my mourning cues were indecipherable. How I wished, in that black hole of clawing grief, that they were readable signs calling for community support when I didn’t have the strength to ask for it.

Victorian mourning culture was as complex as modern-day weddings. Bodies stayed in the family home for extended periods, giving families time to make sense of the same bodies they had always known, now lifeless. Black clothes were standard for up to two years, depending on the relationship with the deceased, after which muted purples and grays were permissible. Death literally colored daily life. After a flu epidemic in 1890, the streets were seas of black and purple foot traffic. Everything from jewelry to stationery to vehicles were marked with mourning symbols, communicating to correspondents and passersby that death had touched the writer of that letter, the person in this carriage. Families hired public mourners to walk with them to the cemetery, a means of asking for community witness to the expansive, enormous, all-consuming nature of private loss. They took one last photograph of their departed, and often clipped hair from their heads to braid into jewelry.

Today, my students often find these practices revolting, but they make sense to me. Ritual pads desperation. It gives us something to hold on to, literally and figuratively, a presence to mark an absence that feels like it will swallow us whole. I too clipped a lock of his hair and stored it away in an envelope to be sent to the few people who still practice the art of weaving Victorian hair jewelry for mourners. It’s not off-putting to me, because it was him—a cherished life connected to mine. It’s the last remaining vestige of his DNA—why wouldn’t I hoard it greedily when I’ve been deprived of every other part of his presence?

At a wedding recently, six months after his death, I found one of his hairs on my dress, death clinging to life at a celebration of love. What is more beautiful than this? This loss, this life, this love, all there together, among a crowd of unwitting wedding guests. I let the strand of hair go, watching as it drifted in the wind. This was another ritual concoction of mine in a world that gave me no structure for my grief, and I used it to wish for a world that did.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!