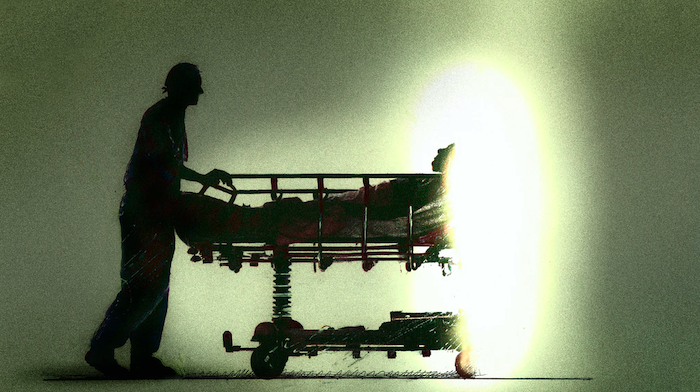

Some hospice agencies have been reluctant to go into homes lately

It was a decision Mika Newton had been dreading, but he knew he needed to stop seeing his mom.

For nearly three years, Newton, an entrepreneur in cancer care advocacy and patient support with his startup xCures, had been taking care of his 79-year-old mother, Raija, who lives near him in Oakland, Calif. When his father passed away, Newton took over caregiving duties for Raija, who suffers from mid-stage dementia and was recently diagnosed with terminal lymphoma. As the coronavirus pandemic exploded in March, Newton’s wife, Nuray, a nurse at Concord Medical Center at John Muir Health, was treating the sudden influx of COVID-19 patients. That meant a halt in Newton’s daily visits to his mom to protect her from any virus transmission.

“I wasn’t able to see her for eight weeks which was hard. But we spoke on the phone every day and I had peace of mind she wouldn’t die alone, because we have full-time home care and hospice for her,” said Newton.

Hospice in the Time of Coronavirus

According to a 2019 National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization report, nearly 1.5 million Medicare beneficiaries currently receive hospice care, defined as compassionate care that replaces treatment for patients who have a terminal condition with less than six months of life expectancy.

However, a National Association for Home Care & Hospice (NAHC) survey conducted in May 2020 found that 95% of hospice agencies have had existing patients refuse visits due to fears of contracting the virus And while two-thirds of hospice agencies are taking COVID-positive patients, they have lost overall clientele, forcing them to reduce direct-care staff. Some staff concerned about their own health and their families’ health are reluctant or even refusing to help any COVID-confirmed patients.

“The agency said they couldn’t risk staff getting the virus and having to be quarantined and out of commission. That was a blow.”

Rebecca Bryan, a journalist for Agence France-Presse based in Los Angeles, realized that hospice care can be a blessing when her father spent eight months in hospice in 2004. But things were different when her 89-year-old mother, Margie, needed hospice before passing away during the pandemic.

“Hospice is a wonderful program, but I never realized how hands on my mom must have been for my dad since I was only home the last month of his life,” said Bryan.

When her mother was recently diagnosed with late stage leukemia and given three to six months to live, Bryan spent two months in Dallas caring for her.

“Mom made a decision not to proceed with blood transfusions, so we secured hospice care for her at home,” Bryan said. But while the small agency in Dallas helped deliver a hospital bed and did an initial inspection, it refused to send any staff to Bryan’s mom’s home when she showed an elevated temperature.

“She had just tested negative for COVID in the hospital and because of her cancer, she had not been outside. She was only at home alone but the agency said they couldn’t risk staff getting the virus and having to be quarantined and out of commission. That was a blow,.” said Bryan.

Bryan said she and her sister learned how to turn her mom to avoid bed sores, put on adult diapers, administer morphine and other paraprofessional caregiving tasks without any instruction.

“That was hard, I wish we had more guidance, because you are constantly asking yourself, ‘Am I doing this right?’” said Bryan.

Hospice Telehealth

Robin Fiorelli, senior director of bereavement and volunteer services for VITAS Healthcare, a provider of end-of-life care, believes in-person hospice care can never really be replaced but that telehealth has become a solution to some hospice challenges during COVID-19.

“We can conduct a virtual tour of a home hospice patient’s living area so our nurses can assess whether a hospital bed, walker, patient lift or bedside commode should be delivered to the home,” said Fiorelli.

“COVID has magnified the strain on family caregivers, there is no relief.”

She also added that face-to-face conversations about goals of care are being replaced by video chats in which physicians, patients and family members explore care-related wishes and document difficult-but-necessary decisions about ventilation, do-not-resuscitate orders and comfort-focused care. This proves especially valuable for family members who live far away from the patient and who can be part of those conversations remotely.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has waived certain requirements for hospice care at home due to the pandemic, such as allowing health care professionals to recertify patients for another six months of hospice care via a telehospice visit, foregoing the mandatory two-week supervisory visit for home health aides and waiving the mandatory hospice volunteer hours, which normally have to meet 5% of total hospice hours delivered.

“COVID has magnified the strain on family caregivers. There is no relief,” said Vic Mazmanian, a dementia care expert who operates Mind Heart Soul Ministry to train faith-based organizations, provide support group services for senior centers and memory care communities and work with hospice chaplains.

“Not being able to take a loved one to adult day care or a senior center so you can get a break is accelerating the stress and impacting the health of caregivers,” said Mazmanian. “The 24/7 nature of hospice care, with most, if not all, the work being done by the family member without help from professionals or volunteers, is being derailed by the pandemic with many caregivers feeling increased anxiety, depression and loneliness.”

From Grief to Gratitude

Mika Newton feels he’s been lucky. In addition to the daily home care for his mom, hospice workers come three times a week. But now that he has resumed his visits, he realizes the stress of not seeing her regularly like before has taken its toll on both of them.

“She’ll ask me why I’m wearing a mask and get angry about it because she doesn’t remember what is happening in the outside world,” said Newton. “Or she’ll forget she has cancer and I have to remind her. I realized the cancer may be killing her, but the dementia is slowly taking her soul.”

Rebecca Bryan advises family caregivers facing hospice for a loved one to ask a lot of questions such as, “If my loved one tests positive for COVID or has one of the virus symptoms, does that affect your ability to come care for them?”

Our Commitment to Covering the Coronavirus

We are committed to reliable reporting on the risks of the coronavirus and steps you can take to benefit you, your loved ones and others in your community. Read Next Avenue’s Coronavirus Coverage.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, many of our patients and their families did not want our professional staff coming into the home. But that has eased up more recently,” said Dr. Kai Romero, chief medical officer for Hospice By the Bay, affiliated with UCSF Health in San Francisco. “We’re proud that throughout this entire experience we have continued to provide needed end-of-life care to everyone on our service and we’ve kept our direct care workers safe with strict testing, PPE and other guidelines. Not one of our staff has tested positive for COVID-19, even though we have had twenty-seven patients who have had the virus.”

COVID-19 Sparks ‘The Talk’ For Families

When Next Avenue asked readers on our Facebook page how the pandemic has affected care for their loved ones, one shared that she recently lost her mom after home hospice care and worked hard to make sure COVID-19 wouldn’t be part of the end of her life.

“Eighty percent of people don’t make a will or have the family conversation about long-term care because they are afraid if they do, they will die,” said Scott Smith, author of “When Someone Dies — The Practical Guide to the Logistics of Death.” Smith, who is CEO of Viant Capital and sits on a hospice board, advises families to have “The Thanksgiving Talk” where older family members share not just their wishes but where all the important legal and financial documentation can be found.

Mika Newton said losing his dad galvanized him and his brother, Timo, to get all his mom’s end-of-life plans settled now, while she’s still alive. “My mom was able to participate in the conversation. which I’m really grateful for. And my dad did a great job making sure she would be OK financially, so it wasn’t a huge burden. I’m glad we went the route with hospice, I feel at peace with it.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!