YES, we’re scared. We’re on the edge, unable to think properly. Our focus flutters and floats around flea-like from one update to the next. We follow the news, because we feel we should but soon we wish we hadn’t, because it’s sad.

The thought of dying alone with a respiratory sickness is so horrifying to hide under our masks. We are separated from one another but we can’t keep our distance from the fear of death. This led me to question, how can I accept my own mortality, so that I can live my life to the fullest during this terrifying situation?

Then I found a novella The Death of Evan Ilyich (1886), by Leo Tolstoy which helped me not only to understand the author’s philosophy towards death but also the psychology behind it. As a result, I could gather some emotional courage to embrace my fear of death during this COVID-19 pandemic situation.

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), a Russian writer, is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time. He is best known for his novels like War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877). But due to his unusual firsthand experiences of death and dying, he also wrote extensively about the inevitability of death for our understanding of life itself. Some of his most memorable meditations on this theme are found in his novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich. In the novella through the story of a dying Russian judge, Tolstoy successfully narrates the different episodes of ‘dying’ some eighty years before its discovery by Swiss-American psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler Ross. In her book On Death and Dying (1969) Kubler Ross outlined five stages that a dying individual goes through.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich, as its title suggests, depicts the death of an ordinary middle-aged Russian judge, but it is also about a man who overcame it. Like everyone in his social circle, Ivan Ilyich lives a superficial life and dedicates his life to climbing the social ladder and seeking the bliss which he believes is found at the top. Initially he was contented with his life but gradually he becomes unhappy as his marriage deteriorates so he starts ignoring his family life and focuses on becoming a magistrate.

One day he falls awkwardly upon hanging curtains for his new home and becomes ill. Doctors offer all kinds of diagnoses and medicines but he cannot recover and within some weeks, Ivan Ilyich could see that he is a bedridden dying man. In his death bed Ivan’s main source of comfort becomes his servant Gerasim. He is the only person in the house who does not fear death, and the only one other than his own son who seems to show compassion for him.

As Ivan’s interaction with Gerasim becomes deeper, Ivan begins to question the how can he accept death without being unhappy? Gerasim guides Ivan in his last days, and allowed him to realise the difference between a superficial and an authentic life and how to accept death with ease. He says, ‘We shall all of us die, so why should I grudge a little trouble?’ Apart from the philosophical thought, Tolstoy also shows the psychological stages of a dying person.

According to Ross, denial is the initial emotional response to the knowledge of death. In this stage people often say, ‘No, not me. It can’t be!’ From chapter five we find Ivan Ilych gets the idea that he is going to die but he could not get used to the idea and immediately denies it. In chapter six he says, ‘It can’t be me having to die. That would be too horrible.’ After a while, he entered the stage of anger, blaming god for imposing this kind of misery and pain to him, and expecting an answer, ‘Why hast Thou done all this? Why hast Thou brought me here? Why, why dost Thou torment me so terribly?’

Then he started talking to god asking for the meaning of his life. During this ‘bargaining’ period he started to look back and after much argumentation with himself he realises that he may not have done anything meaningful during his whole life. Consequently he enters into the ‘black hole’ of depression. He learns that it is impossible to turn back and fight against the forces, now he can only wait for the moment.

Finally, the door of acceptance was opening in his scared mind, with his understanding of the inevitability of death. Ivan Ilyich during this stage realises that he has not lived his life in the best way and he was dead long before he was called to die. He was materialistically driven and blinded most of his life by shallow pleasures. He eventually finds solace from the selfless love and kindness from his family and servants and embraces death. ‘Death is finished,’ he said to himself. ‘It is no more!’

Therefore, The Death of Ivan Ilych is Tolstoy’s parable representing the mystery that living well is the best way to die well. Tolstoy tells us that we don’t fear death, we fear life because we feel that we don’t live our destined time on earth as we were supposed to. It also echoes with the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius who told us that ‘it is not death that a man should fear, but he should fear never beginning to live’.

During this pandemic when we’re feeling the anxieties of infection and death, this story gives us the message of our capacities to respond to the fear of death in ways we never knew we could. It reminds us that, fear isn’t real. It is like wearing the uncomfortable personal protective suit around our mind and feeling we’re being protected.

In doing so, we have allowed this fear into our house, our head, and our heart. It’s circulating like the ghostly virus — looking for prey in every thought and every action. But we must remember that human is not defined by fear. We are a hope and a faith-driven species that seeks to live life to the fullest and not die.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How to prepare for death

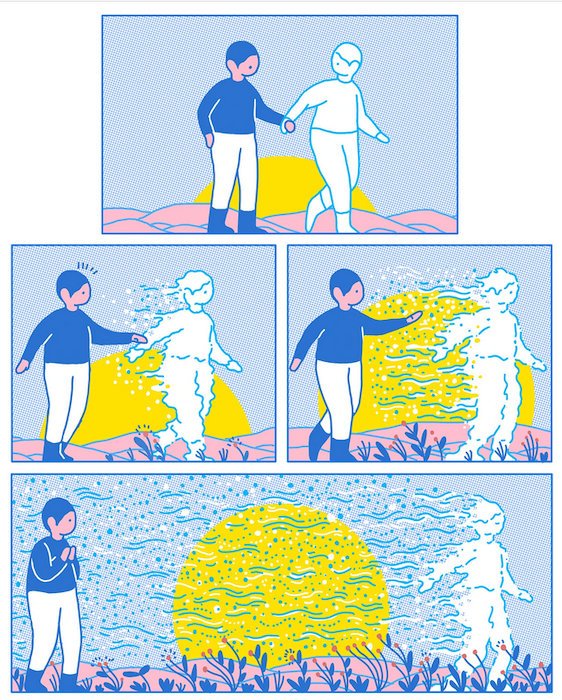

The main challenge in reflecting on one’s own death is the way the various aspects of death and dying are intertwined which make it difficult to discern personal mortality.

First there is the prospect of me dying; of me entering whatever is in store at the end of my life. How long will it last? Will there be pain? What will I leave behind? How do I say goodbye? Next there is the prospect of other people dying, particularly the death of loved-ones and the painful absence their loss leaves behind. How would I cope with the death of a close friend, a partner, a child? But thinking about my dying and other people’s deaths are different. Dying is an event in life, admittedly an important event, but still one that happens within the course of life. Similarly, coming to terms with the loss of a loved-one is an important process, but it belongs to a different domain than my death.

Another temptation is to think of my death as though it is like the death of others. I imagine myself in the shoes of someone as they approach their death. Maybe it would be my soul that is absorbed into a zone of endless tranquility. Maybe it would be my body lying motionless in the coffin. I conjure up images of love-ones with shocked expressions as they are told about my death, I visualize their forlorn looks as they watch my coffin descending into the grave and I picture their reactions to constantly interacting with the spaces I now no longer occupy.

But thinking about my death in terms of what happens when others die does not fully capture what happens when I think about my own death. When I die, looking at myself from the outside, my brain will stop working, my senses will cease to operate, I will no longer have any voluntary control of my muscles, and my body will lie limp and lifeless. This is undeniably what will happen.

Looking at this from the inside is more complicated. If my brain and my body cease to function, then it makes sense to consider my emotions, my consciousness and all those aspects that make up my subjective world, as ceasing to operate as well. My consciousness surely relies on input from my senses plus the processing power of my brain, so without them it is hard to think of how consciousness might persist. I might reassure myself that my consciousness will continue in some form in another realm, but I can’t be sure. It makes more sense to say that when all the conditions for consciousness are no longer present then my consciousness will no longer be able to function.

But this is a terrible thought; a horrifying realization with alarming consequences. My consciousness is always present whenever I look out at anything in the world. I never experience anything around me without being conscious. When I am unconscious, such as when I am asleep or knocked out, I assume the world continues under its own steam, but this is an assumption which I can never fully trust. What I can be surer about is that the world and my consciousness are always paired; they are always together, each interacting with and enabling the other, and participating together in allowing what is going on around me to continue to take place.

What this throws up is the possibility that without my mind the world, and all that it contains—objects, animals, people, loved ones—will cease to exist. In other words, from the standpoint of how I experience things, when I die the conditions that enable the existence of both my consciousness and the world around me will, most likely, no longer be present. In this way, the prospect of my own death highlights the possibility of the end of everything.

The unthinkable and unspeakable nature of my death forces me to walk repeatedly down a conceptual dead-end; a dead-end which discourages any further attempts to think along the same track. Even if we were to consider it important to form some sort of relationship to my death, there is no identifiable object to connect with, there is nothing to cling on to; it stands there as a conceptual black-hole; an emptiness which we can only approach with insecurity and foreboding.

Here lies the true challenge of reflecting on my death; the idea of it as an unthinkable, unspeakable nothingness. But, despite this, thinkers, poets, and artists have, over the centuries, still had a lot to say about personal mortality. It is just too big a part of the rhythm and structure of life to be ignored.

It is, similarly, important for each of us not to turn our backs on death and, despite its unintelligibility, to seek out ways of engaging with it. What is needed is some sort of provisional handhold that allows each of us to reach out and grasp onto something that can enable us to pursue a lifelong relationship with personal mortality.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Grief For Beginners

– 5 Things To Know About Processing Loss

By Stephanie O’Neill

We’re all experiencing some form of grief these days. As this pandemic progresses, more of us will brush shoulders with loss.

The death of someone you care about deeply can be so gut wrenching and annihilating that you may be left unable to imagine ever regaining your equilibrium. And if you’re there right now, just know you won’t be in that painful place forever.

Explore Life Kit

This story comes from Life Kit, NPR’s podcast with tools to help you get it together. To listen to this episode, play the audio at the top of the page or find it here.

I know, because that happened to me in early fall of 2017. That’s when I lost my partner of three years in a motorcycle wreck.

His death flattened me. For two weeks, I couldn’t eat. And for months after the accident, I barely slept, anxiety and exhaustion my constant companions. I came to believe that I’d never crawl out of the desolation.

But with proper care and attention, grief eases its heart-clenching grip. And, says grief expert Terri Daniel, embrace it fully and it can shake you alive and awake like nothing else.

“It’s an opening to a new world, a new self, higher awareness, spiritual growth — whatever you allow to come in,” says Daniel. “And it leads to greater peace in life.”

Daniel knows this firsthand. In 2006, she lost her 16-year-old son to metachromatic leukodystrophy, a rare metabolic disorder.

“It was a progressively degenerative disease. He went from being a perfectly normal kid to in a wheelchair, unable to speak or manage his own body in any way,” she says.

She offers these five strategies to help you cultivate a healthy relationship with grief.

1. Be with your grief.

Tending to grief requires us to be with it, in all its misery and messiness.

“We want to find a place where we can be present with it rather than be in resistance to it,” Daniel says. “It’s an old Buddhist teaching of sitting with uncertainty, sitting with discomfort. And that’s the real tool we need for being with grief.”

It’s not easy. But doing so is key to embarking on the “tasks of grieving,” which span the entire grieving process.

Psychologist William Worden developed the concept, which involves four main tasks: acceptance of the loss, processing that loss, adjusting to life without the deceased person and finding ways to maintain an enduring connection with your loved one as you continue your life.

Daniel suggests thinking of the tasks of grieving as you do other recurring tasks in life. You face the discomfort and do the work because a healthy mourning process demands our presence.

The tasks differ from the “stages of grief” made famous by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. She described the denial, anger, bargaining, depression and finally acceptance that a person goes through when facing their own death.

One thing is certain: Sidestepping grief isn’t an option. Numbing the pain with work, alcohol or other drugs only delays the inevitable, says Sonya Lott, a Philadelphia-based psychologist.

“We have to move through it, or it will continue to show up in insidious ways in every aspect of our being: physically, cognitively, emotionally, spiritually,” says Lott.

2. Grief is a lifelong journey.

The acute pain will subside, but the pain of loss never fully leaves us. It finds us at unexpected moments.

When you’re in the throes of acute grief, this may sound untenable. But Daniel says, given time and space, grief matures into an old, comfortable friend.

It has been more than 13 years since Daniel lost her son. And when a wave of sadness hits her shore, she embraces it.

“I like to say, ‘Hello, grief. … I don’t want you to be here, but I’m going to make friends with you because I can’t get rid of you. So come on in and sit with me, and I will be your friend,’ ” Daniel says. “That’s how you heal. That’s how it strengthens you.”

3. Grief needs expression.

Paint, sculpt, throw clay, dance, bake, journal — whatever feels right. And reach out to trusted friends or family members who get it.

“One of the things a grieving person needs more than anything else is to tell their story and be heard,” she says.

Many people benefit from support groups or time with a grief counselor.

If after a year, you still feel stuck, you could be moving into complicated grief. While regular grief doesn’t usually require therapeutic intervention, that changes with complicated grief, says Lott.

She specializes in treating the condition, also known as prolonged grief disorder. Lott says it’s diagnosed when a person experiences acute grief that interferes with their daily functioning more than a year after the death. A host of factors puts people at risk for complicated grief, Lott says. Among them are multiple losses within a short period, preexisting mental health conditions and unexpected deaths.

For that there’s an evidence-based treatment called complicated grief therapy. You’ll have to find someone like Lott who specializes in this, and it involves between 16 and 20 therapy sessions.

If you need help finding a therapist, there’s a Life Kit for that too.

4. Healthy grieving involves pingponging between loss and restoration.

The journey through grief is not linear.

“So you’re sad, you’re crying, you can’t get out of bed. You’re angry. That’s loss,” Daniel says. “Then you get out of bed and you go write in your journal and take a walk in nature — that’s restoration. Back and forth, back and forth. As long as you’re moving between those two focuses all the time and you’re not stagnant, you’re gonna be fine.”

Eventually, you’ll find yourself residing mostly in restoration, which is healthy but also sometimes brings its own challenges.

“There’s so much guilt that comes with that,” she says. “We feel that holding on to our pain keeps us connected to our loved one, and it’s not true.”

Instead, Daniel and other grief experts urge you to find a positive way of remaining connected. Doing so is one of those important tasks of healing. For some, it’s as simple as framing a favorite photo or planting a tree. For others, it’s getting a tattoo. Or in the case of Daniel, adopting her son Danny’s first name as her last.

5. Grief can break you open to a new you — if you let it.

In early grief, the change to your life is unwelcome. But grief is supposed to change you, Daniel says.

And for many of us, the healing period brings new passions and sometimes an entirely new direction in life. You may find yourself starting a charity, volunteering or going back to school.

For me, it has been to better understand profound grief so that I can continue healing and, when possible, help others through it.

“The term that we use in counseling is ‘meaning-making,’ ” Daniel says. “You make meaning out of your life.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

At New York hospital, a friar watches over those dying

‘The miracle is to let go’

By Kevin Armstrong

The morning after he turned 52 last month, Brother Robert Bathe emerged from the Millennium Hotel on West 44th Street. He ambled half a block into Times Square and reflected on the emptiness. A street cleaner’s whoosh broke the silence.

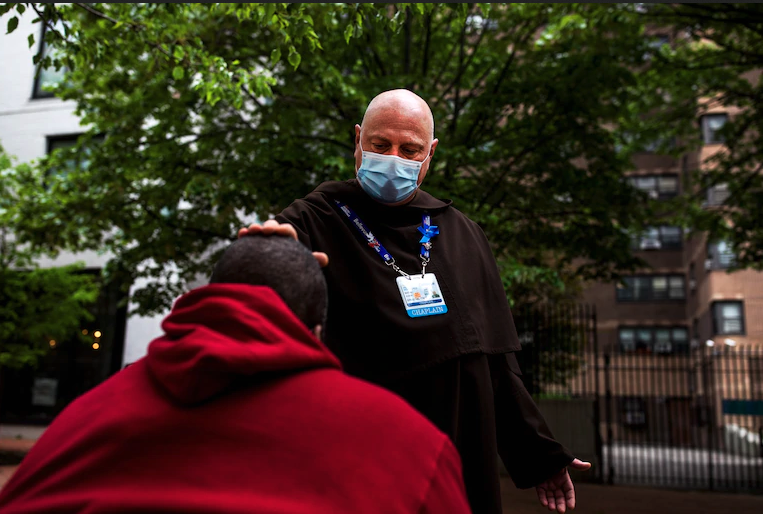

Dressed in a brown robe, the traditional garb of his Carmelite order, Bathe began his daily walk down Broadway. At 28th Street, he hooked left and continued to Bellevue Hospital, where he is a Roman Catholic chaplain and bereavement coordinator.

“Welcome to ground zero,” he said before a nurse trained a thermometer gun on his forehead and scanned for a reading.

It read 98.6. The nurse nodded.

“Normally,” he said, “the family is there with me bedside at death, and when we say the Our Father it is very emotional. Now I stare at a person that is taking their last breaths. I’m with a doctor and a couple of nurses. We’re saying goodbye.”

Bathe is the friar on the front line of the coronavirus pandemic. A native Tennessean who was a soil scientist before entering religious life at age 27, his Southern accent is the first voice many patients’ family members hear from the city’s oldest hospital when he calls to inquire about special needs.

Each morning, he reviews death logs. He then walks through the emergency department and intensive care unit, where he stands behind glass and cues up music on the smartphone he keeps in his pocket. “Bridge Over Troubled Water” is a favorite selection. On Funky Fridays, as he calls them, Bathe mixes Benedictine chants with James Brown. If patients are awake, he flexes his biceps or pumps a fist — encouragement to stay strong. He takes precautions when praying over the intubated, slipping on an N95 mask and face shield. In all, he ministers to more than 25 patients daily.

“Music gives a little more sense of sacredness so I don’t get distracted by nurses and doctors screaming,” he said. “I am focused on that patient, looking at that face. I know who that person is, imagine what it is like for them to be alive.”

His pager pulses with death updates. It is programmed to receive alerts for cardiac emergencies, traumas and airway issues. Whenever a coronavirus patient on a ventilator needs attention, it comes across his screen twice. When a nurse who worked in the neonatal ICU died of covid-19 recently, Mary Ann Tsourounakis, Bellevue’s senior associate director of maternal child health, called pastoral care for help. A group of nurses grieved. First to arrive was Bathe, who led them in prayer in a small hallway.

“One of the most healing and loving I’ve heard,” Tsourounakis said. “People think it has to be a big production. Sometimes those moments are the moments.”

The virus continues to paralyze the city and stretch the limits of its hospital system. Confirmed cases have surpassed 185,000 and more than 20,316 deaths had been recorded, according to the New York City Health Department.

Bathe’s path to New York began in Knoxville, Tenn. He grew up around his grandfather’s cattle farm, went on frequent hikes as an Eagle Scout and eyed a career as a forest ranger while a teenager. His mother, Linda, worked at the University of Tennessee, and she consulted with faculty members about her son’s future in forestry. Prospects were slim, and alternate paths — archaeology or agriculture — were suggested.

He didn’t see himself traveling to Egypt to unearth tombs, so he dug into agricultural studies and toiled with botany and geology as well. Following graduation, he worked for the Buncombe County environmental health agency in North Carolina. Hired to protect groundwater, his release was to drop a line in honey holes for catfish, pitch a tent and listen to bluegrass songs after dark.

One day, Bathe was sent to meet a man named Robert Warren to evaluate his soil so he could build a house. When Bathe arrived, he saw Warren slumped over in his truck. As Bathe approached, he said, Warren grabbed his hand and asked, “Would you pray with me?”

They recited the Lord’s Prayer, he said. Moments later, he was dead, Bathe recalled. Bathe accompanied him to the hospital and attended the memorial service and funeral.

Bathe joined the Carmelites soon after, and in 1997 was assigned to Our Lady of the Scapular and St. Stephen’s Church, two blocks from Bellevue. Lessons followed.

One day, he said, a woman fell from her window in a neighboring building and through the church roof. Bathe was sent up to investigate.

“First dead body I ever smelled,” he says. “Life is tender.”

Transfers are part of the friar life. He taught in Boca Raton, Fla., and served as the vocation director from Maine to Miami before returning to Manhattan two and a half years ago.

In ordinary times, Bathe receives a monthly allowance of $250, lives in the St. Eliseus Priory in Harrison, N.J., and rides the PATH train. He fell ill in January, experienced the chills, registered a temperature of 101 and lost weight. He believed it was pneumonia then and self-isolated, using a back stairwell to his room. His brothers left meals outside his door, and he returned to Bellevue after convalescing. He has yet to be tested for covid-19.

Since March 30, the hospital has facilitated his participation in a program that provides free or discounted rooms for front-line workers, first at a Comfort Inn on the west side of Manhattan and now at the Millennium, to limit his commute. Along the route to work, his bald head, eager gait and hearty laugh are known to mendicants and administrators alike.

He carries on the tradition of the Carmelites, who have ministered at Bellevue since the 1800s, through periodic epidemics, saying Masses from the psychiatric ward to the prison unit. Colleagues include a new rabbi and a 20-year-old imam.

When a Catholic dies, he performs the commendation of the dead, a seven-minute service. His responsibilities range from distributing Communion to finding prayer books for patients across faiths to leading memorial services for staff. He is “staunchly against” virtual bereavement, which has become common amid the pandemic, insisting on providing a physical presence.

“People are looking for a miracle when the miracle is to let go,” he said. “Call me too practical, but I don’t pray they leap out of the grave like Lazarus. I think we’re meant for better. We’re meant for God.”

Hospital staffers are processing what has happened since the pandemic first gripped New York, and they’re bracing for a potential second wave. Since Lorna Breen, medical director for the emergency department at NewYork-Presbyterian Allen Hospital, died by suicide last month, Bellevue has increased its support services for employees. Questions about closure come from all mourners.

“Families ask, ‘Are we going to be able to have our loved one go to Mexico?’ ” Bathe said. “How are we going to do the next step, to bury our loved ones?”

On a recent Sunday, Bathe stepped outside for a breather in what some people call Bedpan Alley, the east side neighborhood that includes hospitals and a shelter on First Avenue. He checked on a homeless woman who sits in a chair facing Bellevue each day, rubbing his thumb against hers as she slept. A shoeless man was prone on the sidewalk. Bathe inquired about a can collector’s economic concerns. Business was slow.

“Are you a priest?” a woman on a bench asked Bathe.

“No, ma’am,” Bathe said. “I’m a friar.”

She introduced herself as Shonda. She was anxious about a meeting with her manager.

“You want to say a prayer for me?” she said.

“Put the phone down,” he said.

Bathe closed his eyes and prayed.

“Breathe,” he said.

“I’m going to breathe,” she said.

As he walked back to the hospital, his pager went off. “Cardiac Arrest,” it read, “10 West 36.”

“Somebody’s dying,” he said.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Kids Are Grieving, Too

Parents are facing difficult moments as children confront the death of a loved one, something they may not fully understand.

By Melinda Wenner Moyer

The coronavirus pandemic has taken more than a quarter of a million lives, many of them mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles and grandparents — adults who have left grieving children behind. Many more children will lose loved ones in the coming months. Here’s some guidance on how to talk to kids about illness and death, and how to support them when someone they love dies.

Be Honest

It can be hard to know how much to share with kids right now. We want to prepare them for what might happen, but we don’t want to needlessly terrify them. Still, if a family member or friend becomes seriously ill, it’s best to be honest about what’s going on, even if you don’t know exactly how things will play out, according to Joseph Primo, the chief executive of Good Grief, a New Jersey-based nonprofit that helps children deal with loss and grief. It’s a good idea, for instance, to tell your kids that grandma has the coronavirus and that even though lots of people are trying to help her, nobody knows whether she will get better.

This honesty might go against your protective instincts, but when we share our feelings and our vulnerability, it makes it easier for our kids to open up about what’s worrying them, and our honesty builds their trust, Primo said.

If someone close to your child is sick, it might also be wise to go over what your family is doing to stay safe, according to Robin Goodman, Ph.D., a certified trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapist based in New York. You might say, “‘That’s why we take care of you, that’s why you wash your hands, that’s why we’re careful when we go outside with a mask,’” Dr. Goodman said. Eileen Kennedy-Moore, Ph.D., a New Jersey-based clinical psychologist and author of “What’s My Child Thinking?,” also emphasized honesty — don’t lie by asserting that you’re all definitely going to be fine. “You can’t give any guarantees, but you can say, ‘my plan is to be around for a very long time,’” she said.

Explain Death

If a loved one dies, it’s best to avoid euphemisms, Primo said. If you tell children that grandpa’s just sleeping or he’s gone somewhere else, they might continue to believe that grandpa will come back or eventually wake up, and not process what happened. “When we try to protect kids by sugarcoating things and not giving them the real information, they end up constructing a narrative that is often far more scary than reality,” Primo said.

Dr. Goodman said that it was best to tell your kids that grandpa died, and then make sure they understand what death means. Tell them, “Once you die, you can’t come back, that your body doesn’t work anymore,” she said. It can help to differentiate what it means to be alive versus dead — to explain that people who are alive can watch TV, brush their teeth, eat and sleep, but that people who are dead cannot.

Correct Misconceptions

Children under 5 probably won’t be able to grasp the permanence of death. They may continue to ask when grandpa is coming back. That’s normal and age-appropriate; just patiently remind them that he died and is not coming back. “It doesn’t mean they’re avoiding it, denying it, not understanding it, it’s because that’s developmentally what they understand,” Dr. Goodman said.

It’s also common for children to worry that they caused a loved one’s death, Dr. Kennedy-Moore said. “The idea that terrible things can happen ‘just because’ is terrifying,” she said. “On some level, it’s painful — but less terrifying — to think that they did something to cause it.” To ease your child’s mind, Primo advises against chiding them or flat-out telling them they’re wrong. Doing so won’t change their mind — it’ll just make them feel like they can’t talk to you about it, he said.

Primo suggested that parents engage with the idea and ask the child why they feel responsible. You want to “explore the thought, keep providing facts delicately, and give them the space and time to process it,” he said. “The kid who gets onto the other side of this thought more quickly is going to be the one who was allowed to live with it for a little bit longer — and to dissect it and to realize, ‘oh, no, that wasn’t me, that’s not how this works.’”

It’s crucial to give your children the opportunity to talk about the death if they want to — and to gently help them understand what happened and why. Dr. Judith Cohen, M.D., a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Drexel University College of Medicine and the medical director of the Allegheny General Hospital Center for Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents in Pittsburgh, witnessed her sister’s sudden death when she was 6, and no one engaged with her about it afterward. “I have a strong belief that when parents don’t talk about it, children develop negative beliefs about what they should have done, what they could have done, and why it happened. That can be very difficult, if not damaging, to their understanding of themselves and the world around them,” she said.

Share Coping Strategies

Funerals aren’t possible for many families right now, so it’s helpful to come up with other ways to remember and memorialize the person who has died. (If a funeral is taking place, you still might want to give your child the option of staying home — not all children like to attend funerals, and that’s OK, Dr. Goodman said.) Maybe you plant a tree in the backyard to remember them, bake their favorite bread, watch their favorite movie or make a special photo album.

Remember, too, that grief doesn’t follow a schedule. American culture expects people to mourn quickly — to cry at the funeral and then feel a sense of “closure” and move on — but these expectations aren’t particularly healthy or appropriate. “Ultimately, the purpose of mourning and memorializing is to foster an ongoing sense of connection with the person who died,” Primo said, and that means “we can memorialize and remember as often as we want.”

It’s also OK for your kids to see you feeling sad and to engage with them about your grief, according to Robyn Silverman, Ph.D., a child and teen development specialist who hosts the podcast “How To Talk To Your Kids About Anything.” “When you talk about your own feelings about anything, it opens the door for the child to talk about theirs — it gives them that permission,” she said.

If your children are having trouble talking about their feelings, Dr. Kennedy-Moore suggested getting out a pack of index cards and asking your child to help you brainstorm various emotions, writing one emotion down on each card (and making sure to include feelings like “sad” and “lonely.”) Then, ask your child to sort the cards into three piles: A “yes” pile (for feelings they’re feeling right now), a “no” pile (for feelings they aren’t experiencing), and a “maybe a little bit” pile. Then, ask them to go through each of the cards in the “yes” and “maybe a little bit” piles, pausing on each one to explain why they believe they are feeling that way. Dr. Kennedy-Moore said that parents should try not to “fix” their children’s feelings or talk them out of having them, but just to briefly acknowledge them. This approach encourages kids to name and engage with their emotions, which “makes those big, messy feelings seem more understandable, and therefore more manageable,” she said. (Sesame Street also has online resources to help children understand and talk about their emotions when they are grieving.)

Support Your Grieving Child

Children often grieve differently than adults — and on a different schedule. They might be upset for a few minutes, and then seem totally fine, and then a few hours later feel sad again. “They grieve deeply, but they don’t hold on to those feelings forever,” Dr. Cohen said. Also, kids may not mourn all that much after they have lost a relative they only rarely saw, and that’s fine. This doesn’t mean they didn’t love them.

If you sense that your child is doing things to avoid engaging with their grief — refusing to talk about grandma or the memories they have of her — “therapy can be helpful,” Dr. Cohen said. Reach out to your pediatrician, a child therapist or a grief counselor for recommendations.

Finally, grieving children can benefit from following a somewhat normal home routine, Dr. Goodman said. This can be tough during a pandemic and especially after a loved one dies — nothing is going to feel normal at that point — but a routine can provide children with a sense of control and reassurance that everything is going to be OK. It tells them that even though things are so very hard right now, life is going to go on.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Who Knows Where the Time Goes

We are all in a box, and in those boxes we are grieving.

Absent any other marker, nature indicates the passage of time. Daffodils and hyacinths give way to roses. Blossoms fall, new leaves bud, pink petals are gone from empty New York streets. Frozen figures in rumpled clothes may note some slight change in the canvas. Who knows where the time goes?

We met in the warm season. We met in the cold season. It becomes possible to imagine time reordered in such a way. Oh, yes, in the warm season, I remember the peonies. A friend tells me her marker of time’s passage in Paris has become the advancing decomposition of a dead rat in the bike lane on her circumscribed daily outing. Who knows where the time goes?

We are all in a box. A smaller or larger Zoom box, depending on the number of people in the conversation. A sidewalk box that sets appropriate social distancing. The box behind the new plastic panels in stores, the box of four too-familiar walls, a mental box of insistent yet unanswerable questions; and in those boxes we are all grieving.

Grieving for a loved one lost to the coronavirus, for lost cities, for lost worlds, for America lost. The virus has revealed a nation in decomposition, incapable of coherence, un-led, angry, disoriented, scattered.

The pathogen itself becomes a political Rorschach test, perceived according to tribal allegiance. The vice president refuses to wear a mask on a visit to the Mayo Clinic, a wink to one of those tribes. Why the heck did the hospital break its own rules and let him in?

Because there are no rules anymore. Who would have thought it is possible to become nostalgic for alternate-side New York parking, that implacable marker of the days? Anything is possible; the proof is before our eyes.

Grieving is not missing. We miss conviviality. We grieve for life. For loves lost and retraced, for the precious moment unappreciated. Perhaps at root we grieve for the failure of our imaginations.

That is to say for our inability to grasp what W.G. Sebald, the German writer, called “the ghosts of repetition,” the ever-recurring patterns of dislocation and disaster that punctuate human history until they impose themselves on the present.

A middle-aged woman sits on the steps of a synagogue sobbing. A young woman props her bike against a fence and sobs. It seems indelicate to intrude on such grief. The loss of time itself can engender a terrible emptiness. I see the clock without hands, and the face without features, in the deserted streets of the shattering nightmare sequence in Ingmar Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries.” Who knows where the time goes?

Speaking of dreams, here is another one. A friend finds herself in a cumbersome crude contraption that looks like a beekeeper’s bonnet but is made of sheets of clear plastic screwed together with wood framing. She cannot figure out why it is there, until she learns that banks now require clients to box their faces in this way to get money from an A.T.M. Perhaps, in intimate circles, the box-bonnet bump will replace the elbow bump.

In our boxes, the great health-versus-wealth debate rages. How, when and where to restart the economy, the appropriateness of this or that trade-off. As if the great trade-offs that produced this dysfunctional America had not already happened.

The trade-offs that disempowered the body politic and democratic practice, and empowered special interests and the wealthy; that starved a health system that might have helped people survive better; that conferred sanctity on soaring executive compensation but not on a decent living wage for the mass of Americans; and on and on and on.

The pandemic is also an urgent call for national and personal reinvention and rebalancing. After the Black Death came the Renaissance. From the depths of economic horror came Roosevelt’s New Deal. From this horror, so far, come the senseless twists and turns of the orange Narcissus.

Bandits hold sway. I have visions of Howard Beale in “Network,” and his I’m-as-mad-as-hell-and-I’m-not-going-to-take-this-anymore that brought screaming Americans to their windows.

“All of humanity’s problems,” said Blaise Pascal, “stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” We are learning. Seeing frenetic consumption for what it was, shuddering at the frantic quest for distraction and status in the time before.

I have been listening to “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” Fairport Convention, 1969, wonderful song, transporting. Turned time’s arrow backward for me, listening to Pink Floyd in Hyde Park in 1968. An ache, we all feel it now.

A cemetery may seem an unlikely source of solace, but Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, ranging over 478 acres, is a beautiful sanctuary. At the main entrance, a large colony of blue-green parrots has established itself. Urban legend has it the birds escaped from a transport at J.F.K. I watched them for a while swooping in mesmeric patterns with twigs in their mouths to add to a multistoried nest that appears to need no additions whatsoever. The parrots get on with their D.I.Y. anyway.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Now more than ever we need to talk about how we want to die

By Dr Anushka Aubeelack

The coronavirus pandemic has brought death and dying to the forefront of the public’s consciousness.

As an anaesthetist working in a London intensive care unit, it is part of my daily life. Within a matter of weeks it has become everyone’s business.

Throughout my career I have been involved in the care of critically-unwell patients. All intensive care doctors accept that in spite of our best efforts, some people will not survive.

Whilst our primary goal is to support patients to recovery, we must also ensure that patients who are no longer benefiting from intensive care are supported too, so they may die without discomfort. This is true of any intensive care ward, at any time, but Covid-19 has further highlighted the importance of good end of life care, as we are seeing record numbers of very unwell people admitted to the hospital.

When the intensive care team is called to admit a patient, we try our best to establish their wishes with regards to treatments.

Have they thought about intensive care and life support? If their heart or breathing was to stop, have they thought about whether they would want the medical team to attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation, for instance?

Whenever we can, we explain clearly what the treatment options are and the risks and benefits of each; we ask them what their own priorities are and answer any questions they may have. Then we adjust the treatment goals to best suit that individual patient.

But sadly, there are times where this communication is not possible and both the team and patient are robbed of that opportunity. That is why I am so passionate about what is known as advance or anticipatory care planning, or what I prefer to call advance life planning.

This is where people are given the opportunity to talk through their priorities and concerns for the end of life and translate them into a plan for their future care and treatment. This may include a Living Will (a legally-binding document also known as an Advance Decision or Directive) to refuse certain treatments and an Advance Statement to record other preferences for care.

People may also wish to nominate a trusted person to make healthcare decisions for them if they become unable to, using a Lasting Power of Attorney for Health and Welfare. These documents are then shared with healthcare professionals and loved ones.

I appreciate that in these uncertain times people can feel powerless and voiceless, but advance care planning can empower you and ensure your voice is heard clearly

All intensivists can recount a story in which, acting in good faith, a patient was put on to full life support, only to subsequently learn from loved ones that this action was against that patient’s end of life wishes.

This is not only heart-breaking for all involved, going against our core belief to ‘do no harm’, but it also denies that person the chance to be kept comfortable in a place of their choosing to say a meaningful goodbye.

This pandemic means we can no longer shy away from death. It is an inevitability of life and conversations about death should no longer be taboo.

It is now more essential than ever to talk to our loved ones about what a good death would mean to us as an individual.

For some, the most important thing might be remaining as pain-free as possible. For others, the priority might be to remain as lucid as possible until the end, or dying in a place of their choosing, whether that is at home or at a hospice, surrounded by their loved ones.

Some may want to accept all efforts to keep them alive as long as possible in spite of the risks. An Advance Statement can record information like this, and while it is not legally-binding like a Living Will, it should be taken into account if decisions need to be made on your behalf about your care and treatment.

I appreciate that in these uncertain times people can feel powerless and voiceless, but advance care planning can empower you and ensure your voice is heard clearly. It also assists medical professionals like myself to continue to act in the best interests of our patients by respecting their wishes.

By recording them as clearly as possible now and sharing them with your family and your GP, you will be far more likely to get the care and treatment that’s right for you when the time comes.

Know that if you do want to put plans in place, you are not alone.

The charity Compassion in Dying – for which I am clinical ambassador – aims to help people prepare for the end of life; how to talk about it, plan for it and record their wishes.

The MyDecisions.org.uk free site, which guides people through different scenarios so they can record their wishes for future care and treatment, has seen the number of completed Living Wills in the last month surge 160 per cent compared to the same period last year, and completed Advance Statements are up 226 per cent.

One might therefore conclude that the coronavirus is prompting people to consider and record their wishes for the end of their lives – some for the first time – and that is to be welcomed.

These are unsettling times, but know that healthcare teams in hospitals will continue to work hard to care for our patients, whether that means supporting them to a full or partial recovery or enabling them to have a dignified death.

For those who have already taken the time to document their wishes for the end of life, I am thankful. To those who are thinking about it, I appeal to you to do so.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!