The only guarantees in life are taxation and death, according to Benjamin Franklin. For Ellen Arrison of New Salem, that reality is literally sitting inside her living room right now — in the form of a rectangular pinewood coffin.

“I hope it has lots of coffee rings and wine stains on it before I have to use it,” said Arrison, who was one of a dozen participants who took part in a recent coffin-making workshop in Greenfield that was co-sponsored by was co-sponsored by Green Burial Massachusetts and the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Western Massachusetts. According to Arrison, an experienced hospice nurse, making a coffin “made death more real” and caused her to confront end-of-life questions — a subject that she says is taboo in western culture.

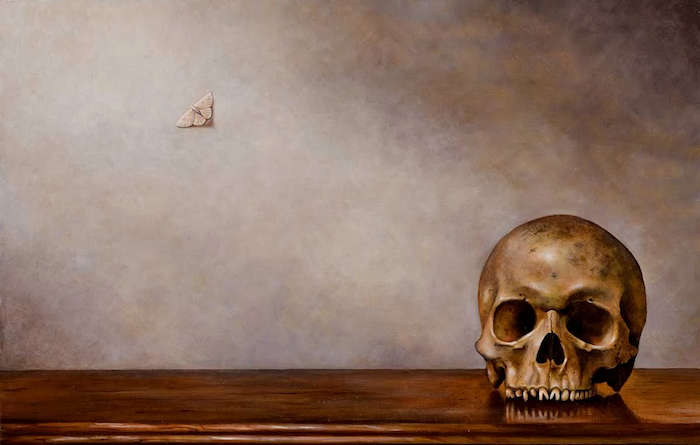

“We’re all going to die, but we don’t believe it. Part of life is appreciating the time there is,” said Arrison. Housing the coffin in her living room serves as “a conversation starter” and is a constant reminder of her own mortality. She intends to keep it there until it needs to be used for its intended purpose.

“I knew I wanted a green burial, so that’s part of it too,” Arrison said. “I live in a rural area and I’d like to be buried in my own land. I love it and I’ve spent a lot of time and energy and money — I’d like to give back to the land.”

The coffin making workshop, which was led by Joan Pillsbury of Greenfield, treasurer of Green Burial Massachusetts, a nonprofit advocacy group, cost $210 and covered about two to three hours. Participants made “quick coffins” with pine provided by carpenter Chuck Lakin of Waterville, Maine, who also provided the tools and oversaw the construction process, Pillsbury said. The workshop drew people from varied walks of life.

“Everyone’s skilled were varied. Some people had no experience with tools, some could have finished the project in an hour,” Lakin said. “I tried to explain and guide people through the process.”

Afterward, the group, like pallbearers, “made a ceremony out of carrying their coffins to their vehicles,” Lakin said.“Everyone would carry a coffin to someone’s car, then that person would drive and park. Then they would do the same thing with someone else’s coffin. It must have been a sight for someone just passing by.”

Don Joralemon, a retired Smith College anthropology professor, is keeping his coffin in the basement of his home in Conway. He said he decided to make a coffin because he “isn’t a fan of the funeral industry” and he wanted to take the burden away from his family when the time comes.

“I hope to make use of it in land in Conway,” Joralemon said. “It’s a simple process. You have to get permission from the Board of Health and there needs to be a permanent indication that there’s a grave on the property.”

He said the experience of building the coffin was wonderful and he would recommend it to anyone.

The craft of coffin making

Before making coffins, Lakin, who said he’s been a woodworker since he was 26 when he got out of the United States Navy, made a living as a librarian at Colby College. When his father was dying, Lakin said he spent the last six weeks of his life surrounded by family and loved ones. It was a very personal and moving experience, Lakin said.

“He was in his own bed with each of his family touching him when he passed,” he recalled.

After, his family called a funeral home and his father’s body was taken away.

“He was hauled away and I hated it because it had been so personal and all of a sudden he was gone,” said Lakin.

Later on, Lakin read a manual about how to take care of a loved one after they have died. The book included instruction on how to wash, present and bury someone after death. Before, Lakin noted, “I hadn’t thought of what was next.”

“That’s when I began talking about these things with people,” he continued. “Not to convince them of what to do, but to provide information so they can have the experience I wanted to have.”

He decided to try his hand at making coffins so that others wouldn’t experience the emptiness that he felt. These days, Lakin says he makes between three and five coffins a year and uses the money he makes to travel to events throughout Maine and talk about the options people have funerals.

“People have no idea they have as many options as they do,” Lakin said.

He met Pillsbury at one of these events, the annual Funeral Consumers of Maine, and agreed to hold the coffin-making workshop. If there was enough interest, Lakin says he’d be willing to put on another workshop in the future.

A healing endeavor

For Lakin and the workshop participants, building the coffins was a way of confronting their mortality head-on. According to Lakin, Americans are proficient at ignoring the reality that they are going to die someday.

“You have to recognize and admit it is going to happen,” Lakin said. “It’s a natural part of life; there’s a transition in and there’s a transition out. It happens to everyone. … Your attitude toward it and preparation makes all the difference. It turns what could be a tragedy into a spiritual experience.”

Lakin was speaking from personal experience. When his wife, Penny, died in 2017, Lakin held the funeral at their home. He said he wife was in their house for the last five weeks of her life and, for the duration of those weeks, it was like a “long party.”

“We have a good support group, and we told them to stop by anytime,” Lakin said. “Sometimes there would be 12 people in the living room.”

After her death, Lakin said that two of her best friends anointed and dressed the body. Lakin built her coffin and invited guests to come over and draw and write messages on it. Then after four days, which included a time to display the body, they held a burial ceremony followed by dinner at her favorite restaurant.

“We offered people the ability to do something physical — writing or drawing something — to help them (grieve),” said Lakin. “They were grieving and I don’t think they knew what they were going through.”

Arrison had a similar experience with a home burial as a child after a friend’s grandfather died.

“He was laid out in the living room for three days,” Arrison said, noting, “I, personally, find the idea of viewing a body when it’s presented in an artificial way macabre. It makes it seem disconnected in some way.”

Green burials and the death positive movement

The term “death positive” might seem like an oxymoron, but those who are a part of a growing movement of the same name say it’s an effort to demystify mortality in American culture.

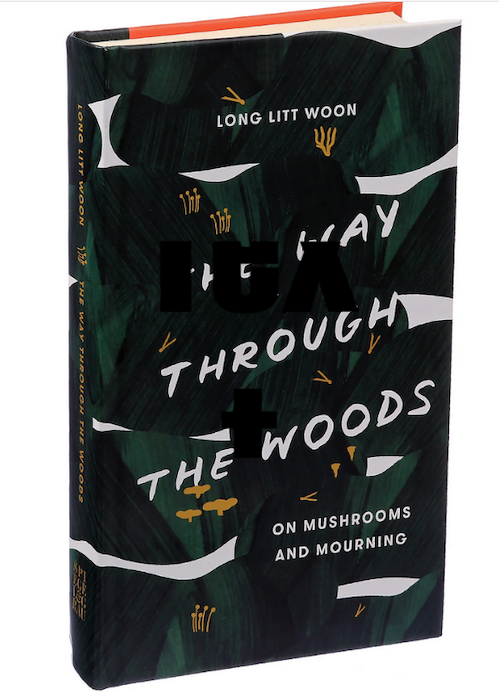

Joralemon, the retired Smith professor who attended the workshop, covered the topic in his book titled “Mortal Dilemmas: The Troubled Landscape of Death in America.” Americans have made death into a taboo subject, he says. But it hasn’t always been that way.

“It didn’t use to be so bad. Deaths would happen in the home. The body would be washed, coffins would be made by a carpenter. It wasn’t a surprise or taboo,” Joralemon said. “Then the profession of funeral director was made when more people were dying in hospitals.”

In contrast to culture’s perspectives on death, he said it’s imperative that people confront their own mortality.

“Life is a transformation and death is part of it,” Joralemon said. “Bit by bit, hopefully, we can start to recover the comfort with death and celebrate the moments before that.”

Along with the workshop, Arrison noted that her experience as a nurse has helped normalize the idea of death.

“I did hospice care for some time and I’ve been with people in the process of dying,” Arrison said. “It was valuable and a privilege. It also makes the inevitability (of death) more real. It’s familiar when it’s happening to someone else. I think that the experience is not difficult or frightening, it’s interesting and curious.”

“You get a health care proxy, a will, build your coffin,” Arrison said. “These activities take some of the dread out of it. It normalizes it and you appreciate the time you have — it’s a procrastination deterrent.”

More than preparation for the end of her life, knowing that she’s going to die someday “softens my heart,” Arrison said. “I know that every person is going to die, too. It enhances the experience of life. I have a more positive perspective. It’s actually life-affirming.”

Lakin said he learned about the term “death positive” from Caitlin Doughty, a mortician and funeral home director in Los Angeles, California, who made videos answering questions about death and dying.

“She started by answering people’s basic questions about death, then she ran out of common questions and had to look for topics,” Lakin said. “I found it informative and entertaining because she has a sarcastic sense of humor. I don’t think she coined the term ‘death positive,’ but I think she popularized it.”

He said the death positive movement coincides with a similar trend called the “green burial movement.” Both stress a more personal quality to end-of-life care.

Green Burial Massachusetts is a grassroots organization that educates people about green burials — where a person is not embalmed and put into a coffin or shroud that will biodegrade along with the body. The person is buried about 3 ½ feet in the ground, where aerobic decomposition can occur.

“A burial will happen on a piece of land 3 ½ feet under the ground, where the person isn’t embalmed and there’s no concrete,” Lakin said. “Everything is biodegradable — the person can be buried in a shroud, a coffin, a cardboard box. They also typically use stone from the area as monuments, engraved with the names and dates.”

Joralemon said his philosophies align with the green burial movement because “this is what we did for millennia and there’s no reason not to set aside land for people who would like a green burial.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!