[S]haring your “bucket list” could be easier than discussing end-of-life medical preferences, and it might be just as useful to your physician, researchers suggest.

If you, like many Americans, have a “bucket list,” your doctor would be well-served by learning its contents, according to Stanford University researchers, who say a conversation about these goals might help guide future care.

Their study, published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine, found that 91 percent of participants had a “bucket list,” or a list of things they hope to do before they die.

Researchers say the bucket list conversation is a simple strategy to help patients consider health decisions. In learning these goals, clinicians are better suited to promote informed decision-making when discussing the potential impact of treatment options.

“The number one emotion I see in patients when they are dying is regret,” said study author VJ Periyakoil, director of the Stanford Palliative Care Education and Training Program in California.

Her team’s online survey asked more than 3,000 participants nationwide if they had a bucket list and what was on it, in order of importance. The average participant was about 50 years old.

Travel was the most prevalent desire. More than 78 percent submitted travel-related hopes. Among college-educated women, 84 percent had destinations in mind.

Accomplishing a goal, like finishing a degree and learning to swim, was important to about 78 percent.

Roughly half hoped to achieve milestones, like getting married, celebrating an anniversary and reconnecting with old friends.

Desire to spend quality time with friends and family ranked fourth, followed by hope for financial stability.

Daring activities turned up on 15 percent of lists. Respondents 25 and younger were much more likely to report daring activities, such as skydiving and swimming with sharks.

Participants who said religion or spirituality was important were the most likely to have a bucket list.

“Faith allows you to imagine something that cannot be verified,” Periyakoil explained. “The ability to imagine something is a proxy for a level of hope even in the face of little evidence. Those are the people who have things on their list and hope they can do them.”

The researchers did not have participants share their lists with physicians, nor did they ask physicians for their opinions on the idea of sharing patients’ bucket lists. Furthermore, the survey did not target people living with chronic or terminal disease.

Still, the researchers hope their findings will help shift end-of-life planning away from an over-reliance on documents.

“If we look at advance directives as the savior of our health system, it’s not going to work,” Periyakoil said. “I don’t want to wait for my doctor to tell me it’s time to do my advance directive. I would rather go to the doctor and say what’s on my bucket list.”

Such a discussion is more intimate than the more sterile conversations that sometimes accompany advance directives, said Susan Mathews, a bioethicist, nurse and instructor at Indian River State College in Fort Pierce, Florida.

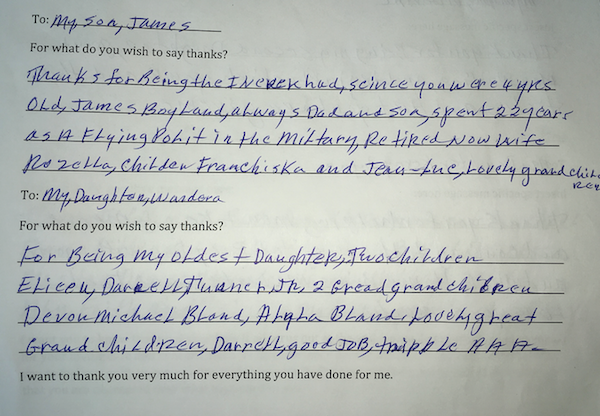

“Advance directives are about death; a bucket list is about living,” Mathews said. “A bucket list, if prepared with a dose of serious reflection, gets to the heart of our relationship with self and the others for whom we care.”

Patients should still complete advance directives, she said, but with periodically updated companion documents that express goals.

Like advance directives, bucket lists can change.

The changing of a patient’s health status is one concern with the bucket list strategy, according to medical anthropologist Craig Klugman, who teaches classes on death and dying at DePaul University in Chicago. “Being asked about a bucket list could create anxiety that they should have a list and take efforts to fulfill it,” Klugman said.

Periyakoil said, too often, physicians don’t realize what patients want from life. If they ask about these desires, they can avoid the clinical vacuum in which treatment plans are too often made.

“We need patients to understand that it’s their life, have a better understanding of what they want to do, and understand that medical procedures are a pathway they are signing into,” Periyakoil said.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!