After death, there are four main tasks that need to happen before the burial. These can be achieved with the help of a funeral home or with the help of loved ones facilitating a home funeral. Learn what needs to take place between death and burial and the role of a funeral home versus a home funeral during the process.

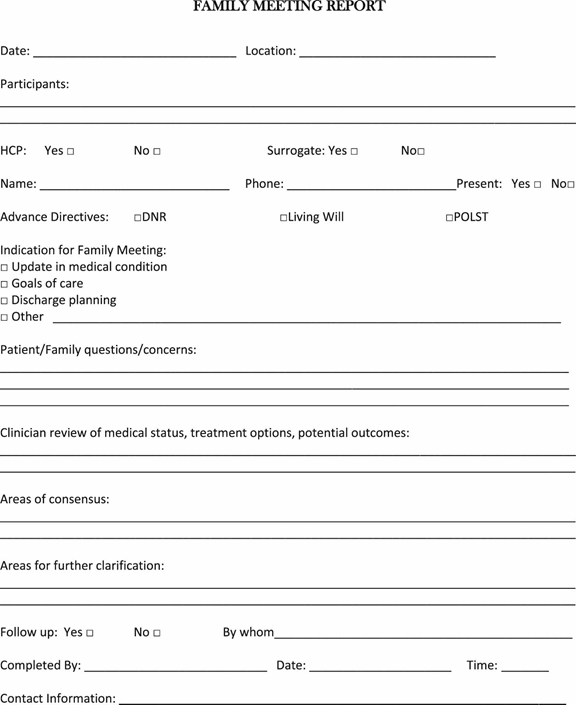

When preparing for death, many people know that there are options for how a person is treated as they are dying. Documents may be completed, hopefully well in advance of the dying process, to express those personal wishes. Documents may include a Living Will, Health Care Power of Attorney, or 5-Wishes. Few know that there are options for after-death care. There are 3 options for the disposition of the body between death and interment or cremation:

Option 1: Hire a funeral home to carry out all aspects of after-death care, including transportation, refrigeration, initiation of death certificate, obituary, cremation and/or transportation to place of burial, and coordination of set up at cemetery for the graveside service.

Option 2: Hire a funeral home to carry out some of the above mentioned aspects of after-death care and take care of other details utilizing family and friends.

Option 3: Have family and friends direct the details of after-death care. This process is call a Home Funeral.

Four Main Tasks

Regardless of which option you choose for after-death care, four main tasks will need to take place between death and burial:

- Transportation From Place of Death: The body may need to be moved from the place of death (such as a hospital/nursing facility or home) to the place of after death care (either a home or a funeral home).

- Care of the Body: The body will need to be cared for until the time of burial. This care may include bathing, dressing, refrigeration or dry ice application, and perhaps wrapping in a shroud before cremation or burial.

- File Death Certificate: A death certificate will need to be filed. This includes gathering the information to complete the certificate, signature from attending physician, and filing with the county registrar.

- Transportation To Burial Site: The body will need to be transported from the place of care to Carolina Memorial Sanctuary when it’s time for the burial.

Between Death & Burial: Four Tasks

Before we go over the four steps that take place between death and burial, it’s important to understand the difference between a funeral home and a home funeral. If you’re not clear on the differences, read this page first.

The four tasks between death and burial are pretty detailed, so we’ve created the following graphic to help show your options. Scroll down to see a written explanation of the four main tasks.

Task 1: Transportation From Place of Death

Death can occur anywhere but will often occur at home, in a hospital, or in a hospice center. For unexpected deaths, the body is often brought to a hospital to be examined by the medical examiner. Depending on whether you’re opting for a home funeral or the assistance of a funeral home, the body will need to be transported to the place of care.

Funeral Home

If you hire the assistance of a funeral home, they will come to the place of death and pick up the body and take it to the funeral home for care.

Home Funeral

If you are having a home funeral, you can pick up the body from a hospital, hospice center or morgue and bring it home yourself. You also have the option of hiring a funeral home to pick up the body and transport it to the home for you. If you choose to pick up the body yourself, CEOLT is happy to act as a liaison to help that transition go smoothly.

Task 2: Care of the Body

Until the time of burial, the body will need to be cared for and kept cool. Again, this can be done at home or at a funeral home.

Funeral Home

Once a funeral home has picked up the body and brought it to their facility, they will then clean and dress and/or shroud the body. Afterward, the body will be placed in refrigeration to keep it cool until the day of burial, at which point the body will be transported to the burial site.

Home Funeral

For home funerals, once the body has been transported to the house, the body is first cleaned and then dressed and/or shrouded, and then placed in a room where the body can rest and where friends and family can visit if they choose. To keep the body cool, dry ice is usually employed. Certain traditions and spiritual faiths observe the practice of allowing the body to lie in state for multiple days. Using proper care, a body can be kept in the home for multiple days without issue until the time of burial. There are exceptions to this and having the support of an experienced person from CEOLT or going through the home funeral course will help to address the circumstances that could arise. Caroline Yongue, our Director, has been assisting families with home funerals for over 20 years, and has rarely encountered a situation where a home funeral wasn’t possible.

Task 3: File Death Certificate

While the body is being cared for and waiting for burial, a death certificate will need to be filed.

Funeral Home

If going the route of a funeral home, they will file the death certificate for you. You will need to provide personal information of the deceased.

Home Funeral

If doing a home funeral, an individual who is assisting will need to file the death certificate. This includes gathering the personal information for the deceased, obtaining the signature and cause of death from the attending physician and filing the death certificate with the County Registrar (in the county where death happened).

Task 4: Transportation To Burial Site

The final task to carry out will be to transport the body to the burial site just prior to the time of burial. The date of burial will need to be coordinated with Carolina Memorial Sanctuary in advance so that we can prepare the grave and prepare for the service.

Funeral Home

On the date of the burial, the funeral home will transport the body to Carolina Memorial Sanctuary usually 30-60 minutes before the service is scheduled to begin. They will either release the body to Carolina Memorial Sanctuary or transport the body to the gravesite, depending on the circumstances.

Home Funeral

Just like with the first transportation, from the place of death to the place of care, getting the body from the home to the Carolina Memorial Sanctuary can be done by friends/family assisting with the home funeral or a funeral home can be hired for this service. Carolina Memorial Sanctuary will consult with you and recruit the help of volunteers if additional hands are needed to transport the body from the vehicle to the gravesite.

Final Thoughts: Saying Goodbye Before the Body Is Taken Away

We want to end by sharing some final thoughts on saying goodbye to your loved ones. Contrary to popular belief, the body does not have to be whisked away the moment death occurs. When death occurs at home, most people believe that they are obligated to immediately call 911 or a funeral home so they can quickly transport the body away. Or if a loved one has died at a hospital or hospice center, there may even be pressure from the staff to have the body removed. If you have decided to use a funeral home and the body will not be coming back home, you have the right to ask to spend time with the body of your loved one and say goodbye before the body is transported away from your home/the hospital/hospice center. The opportunity and time to say goodbye can be very healing and beneficial and help with closure and grieving. If a loved one dies at home, you can let the funeral home know that you would like some time with your loved one before they come to pick them up. It doesn’t even have to be the same day (this is known as a “delayed pickup”). If a loved one dies at a hospital or hospice center, let the staff know that you would like time with your loved one. They will often allow a number of hours for this to take place. You even have the option of having the funeral home bring the body to the home for goodbyes, and then have them transport the body to the funeral home for care and refrigeration before burial. Last – you always have the option of going to the funeral home and having your goodbyes there. The time after death is the last time some people have to see their loved ones and say goodbye – so be sure to ask for what you want and what you need and know that you can take your time.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!