What Happens Inside a Dying Mind?

[W]hat makes a person believe that he visited heaven? Is there a way for science to get at what’s really going on? In the April 2015 issue of the Atlantic, Gideon Lichfield mounts an empirical investigation of near-death experiences, concluding that more rigorous research must be pursued to understand what happens in the minds of “experiencers,” as they call themselves. One thing is abundantly clear, though. Near-death experiences are pivotal events in people’s lives. “It’s a catalyst for growth on many different levels—psychologically, emotionally, maybe even physiologically,” says Mitch Liester, a psychiatrist.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Learning To Advance The Positives Of Aging

[W]hat can be done about negative stereotypes that portray older adults as out-of-touch, useless, feeble, incompetent, pitiful and irrelevant?

From late-night TV comedy shows where supposedly clueless older people are the butt of jokes to ads for anti-aging creams equating youth with beauty and wrinkles with decay, harsh and unflattering images shape assumptions about aging. Although people may hope for good health and happiness, in practice they tend to believe that growing older involves deterioration and decline, according to reports from the Reframing Aging Initiative.

Dismal expectations can become self-fulfilling as people start experiencing changes associated with growing older — aching knees or problems with hearing, for instance. If a person has internalized negative stereotypes, his confidence may be eroded, stress responses activated, motivation diminished (“I’m old, and it’s too late to change things”) and a sense of efficacy (“I can do that”) impaired.

Health often suffers as a result, according to studies showing that older adults who hold negative stereotypes tend to walk slowly, experience memory problems and recover less fully from a fall or fracture, among other ramifications. By contrast, seniors whose view of aging is primarily positive live 7.5 years longer.

Can positive images of aging be enhanced and the effects of negative stereotypes reduced? At a recent meeting of the National Academies of Sciences’ Forum on Aging, Disability and Independence, experts embraced this goal and offered several suggestions for how it can be advanced:

Become aware of implicit biases. Implicit biases are automatic, unexamined thoughts that reside below the level of consciousness. An example: the sight of an older person using a cane might trigger associations with “dependency” and “incompetence” — negative biases.

Forum attendee Dr. Charlotte Yeh, chief medical officer for AARP Services Inc., spoke of her experience after being struck by a car and undergoing a lengthy, painful process of rehabilitation. Limping and using a cane, she routinely found strangers treating her as if she were helpless.

“I would come home feeling terrible about myself,” she said. Decorating her cane with ribbons and flowers turned things around. “People were like ‘Oh, my God that’s so cool,’” said Yeh, who noted that the decorations evoked the positivity associated with creativity instead of the negativity associated with disability.

Implicit biases can be difficult to discover, insofar as they coexist with explicit thoughts that seem to contradict them. For example, implicitly, someone may feel “being old is terrible” while explicitly that person may think: “We need to do more, as a society, to value older people.” Yet this kind of conflict may go unrecognized.

To identify implicit bias, pay attention to your automatic responses. If you find yourself flinching at the sight of wrinkles when you look in the bathroom mirror, for instance, acknowledge this reaction and then ask yourself, “Why is this upsetting?”

Use strategies to challenge biases. Patricia Devine, a professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies ways to reduce racial prejudice, calls this “tuning in” to habits of mind that usually go unexamined.

Resolving to change these habits isn’t enough, she said, at the NAS forum’s gathering in New York City: “You need strategies.” Her research shows that five strategies are effective:

- Replace stereotypes. This entails becoming aware of and then altering responses informed by stereotypes. Instead of assuming a senior with a cane needs your help, for instance, you might ask, “Would you like assistance?” — a question that respects an individual’s autonomy.

- Embrace new images. This involves thinking about people who don’t fit the stereotype you’ve acknowledged. This could be a group of people (older athletes), a famous person (TV producer Norman Lear, now 95, who just sold a show on aging to NBC) or someone you know (a cherished older friend).

- Individualize it. The more we know about people, the less we’re likely to think of them as a group characterized by stereotypes. Delve into specifics. What unique challenges does an older person face? How does she cope day to day?

- Switch perspectives. This involves imagining yourself as a member of the group you’ve been stereotyping. What would it be like if strangers patronized you and called you “sweetie” or “dear,” for example?

- Make contact. Interact with the people you’ve been stereotyping. Go visit and talk with that friend who’s now living in a retirement community.

Devine’s research hasn’t looked specifically at older adults; the examples above come from other sources. But she’s optimistic that the basic lesson she’s learned, “prejudice is a habit that can be broken,” applies nonetheless.

Emphasize the positive. Another strategy — strengthening implicit positive stereotypes — comes from Becca Levy, a professor of epidemiology and psychology at Yale University and a leading researcher in this field.

In a 2016 study, she and several colleagues demonstrated that exposing older adults to subliminal positive messages about aging several times over the course of a month improved their mobility and balance — crucial measures of physical function.

The messages were embedded in word blocks that flashed quickly across a computer screen, including descriptors such as wise, creative, spry and fit. The weekly sessions were about 15 minutes long, proving that even a relatively short exposure to positive images of aging can make a difference.

At the forum, Levy noted that 196 countries across the world have committed to support the World Health Organization’s fledgling campaign to end ageism — discrimination against people simply because they are old. Bolstering positive images of aging and countering the effect of negative stereotypes needs to be a central part of that endeavor, she remarked. It’s also something older adults can do, individually, by choosing to focus on what’s going well in their lives rather than what’s going wrong.

Claim a seat at the table. “Nothing about us without us” is a clarion call of disability activists, who have demanded that their right to participate fully in society be recognized and made possible by adequate accommodations such as ramps that allow people in wheelchairs to enter public buildings.

So far, however, seniors haven’t similarly insisted on inclusion, making it easier to overlook the ways in which they’re marginalized.

At the forum, Kathy Greenlee, vice president of aging and health policy at the Center for Practical Bioethics in Kansas City and formerly assistant secretary for aging in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, called for a new wave of advocacy by and for seniors, saying, “We need more older people talking publicly about themselves and their lives.”

“Everybody is battling aging by themselves, reinforcing the notion that how someone ages is that individual’s responsibility” rather than a collective responsibility, she explained.

Underscoring Greenlee’s point, the forum didn’t feature any older adult speakers discussing their experiences with aging and disability.

In a private conversation, however, Fernando Torres-Gil, the forum’s co-chair and professor of social welfare and public policy at UCLA, spoke of those themes.

Torres-Gil contracted polio when he was 6 months old and spent most of his childhood and adolescence at what was then called the Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children in San Francisco. Back then, kids with polio were shunned. “It’s a real tough thing to be excluded,” he remembered.

His advice to older adults whose self-image is threatened by the onset of impairment: “Persevere with optimism. Hang in there. Don’t give up. And never feel sorry for yourself.”

Now age 69, Torres-Gil struggles with post-polio syndrome and has to walk with crutches and leg braces, which he had abandoned in young adulthood and midlife. “I’m getting ready for my motorized scooter,” he said with a smile, then quickly turned serious.

“The thing is to accept whatever is happening to you, not deny it,” he said, speaking about adjusting attitudes about aging. “You can’t keep things as they are: You have to go through a necessary reassessment of what’s possible. The thing is to do it with graciousness, not bitterness, and to learn how to ask for help, acknowledging the reality of interdependence.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Toronto vet helps pets to pass in comforts of home

[A]t first, they open the door to their home and greet me with “you have the worst job in the world”, followed by “how do you do this?”

They are pet owners and they are referring to the fact I am a hospice veterinarian. I am at their home because I am a mobile hospice veterinarian. I am at their home to help them say goodbye to their most loved companion, their family dog or cat.

When I enter their home, people often apologize for the dirty dishes still in the sink or the mess on the floor. I am blind to their clutter and I never judge them on the cleanliness of their home. What I do notice are the blankets and pillow on the couch.

You see, when an older pet is no longer able to make it upstairs to the owner’s bed, the owner’s bed gets moved to the family room couch. These are some of the final precious moments owners have with their pet and they don’t want to miss out on any of it by sleeping apart for their last few weeks or days together. It is a slumber of true love.

Goodbye at home is a gift

Being able to say goodbye at home is a gift people can provide to their beloved aging pets. Veterinary Aid in Dying, euthanasia or putting a pet to sleep are all terms for the final act of love pet parents are often called on to do for a pet that is suffering. This suffering may be physical and/or emotional and can deeply affect the owner as well.

From the Greek translation, euthanasia literally means “good death”. Our pets are most deserving of a good death, especially after the unconditional love and dedication they showered upon us during our memorable lives together.

When I began my in-home hospice and palliative care service, my goal was to ensure everyone had the opportunity to allow their pet to pass with dignity and love.

Comfort and privacy

Today, along with three other compassionate veterinarians, we are able to provide this service to pets and their owners in the comfort and privacy of their homes. Being able to provide this personal and meaningful service is an honour and responsibility I don’t take lightly.

Home is where the heart is and home is where the dog is. This is their safe space, their favourite place. This is where they lived and this is where they should be allowed to die.

Euthanasia at home, performed by a skilled veterinarian, ensures our pets are not stressed, are not in pain and have a peaceful, love-filled passing. Something they no doubt deserve, and something we all hope for ourselves.

So now, by the time I leave, “you have the worst job in the world” changes to “what an emotionally rewarding job you have” and “how do you do this?” changes to “thank you for doing this”.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What ancient cultures teach us about grief, mourning and continuity of life

[A]t this time of the year, Mexican and Mexican-American communities observe “Día de los Muertos” (the Day of the Dead), a three-day celebration that welcomes the dead temporarily back into families.

Festivities begin on the evening of Oct. 31 and culminate on Nov. 2. Spirits of the departed are believed to be able to reenter the world of the living for a few brief moments during these days. Altars are created in homes, where photographs

and other personal items evocative of the dead are placed. Offerings to the deceased include flowers, incense, images of saints, crucifixes and favorite foods. Family members gather in cemeteries to dine not just among the dead but with them. Similar traditions exist in different cultures with different origins.

As scholars of death and mourning rituals, we believe that Día de los Muertos traditions are most likely connected to feasts observed by the ancient Aztecs. Today, they honor the memory of the dead and celebrate the continuity of generations through loving reunion with those who came before.

As Western societies, particularly the United States, move away from the direct experience of a mourner, the rites and customs of other cultures offer valuable lessons.

Loss of rituals

Funerals were handled in the home well into the 20th century in the U.S. and throughout Europe. Sometimes, stylized and elaborate public deathbed rituals were organized by the dying person in advance of the death event itself. As French historian Philippe Ariès writes, throughout much of the Western world, such death rituals declined during the 18th and 19th centuries.

What emerged instead was a greater fear of death and the dead body. Medical advances extended control over death as the funeral industry took over management of the dead. Increasingly, death became hidden from public view. No longer familiar, death became threatening and horrific.

Today, as various scholars and morticians have observed, many in American culture lack the explicit mourning rituals that help people deal with loss.

Traditions in ancient cultures

In contrast, the mourning traditions of earlier cultures prescribed precise patterns of behavior that facilitated the public expression of grief and provided support for the bereaved. In addition, they emphasized continued maintenance of personal bonds with the dead.

As Ariès explains, during the Middle Ages in Europe, the death event was a public ritual. It involved specific preparations, the presence of family, friends and neighbors, as well as music, food, drinks and games. The social aspect of these customs kept death public and “tame” through the enactment of familiar ceremonies that comforted mourners.

Grief was expressed in an open and unrestrained way that was cathartic and communally shared, very much in contrast with the modern emphasis on controlling one’s emotions and keeping grief private.

In various cultures the outpouring of emotion was not only required but performed ceremonially, in the form of ritualized weeping accompanied by wailing and shrieking. For example, traditions of the “death wail,” which allowed people to cry their grief aloud, have been documented among the ancient Celts. They exist today among various indigenous peoples of Africa, South America, Asia and Australia.

In a similar way, the traditional Irish and Scottish practices of “keening,” or loudly wailing for the dead, were vocal expressions of mourning. These emotional forms of sorrow were a powerful way to give voice to the impact of individual loss on the wider community. Mourning was shared and public.

In fact, since antiquity and throughout parts of Europe until recently, professional female mourners were often hired to perform highly emotive laments at funerals.

Such customs functioned within a larger mourning tradition to separate the deceased from the world of the living and symbolize the transition to the afterlife.

Rituals of celebration

Mourning rituals also celebrated the dead through carnival-like revelry. Among the ancient Greeks and Romans, for example, the deceased were honored with lavish feasts and funeral games.

Such practices continue today in many cultures. In Ethiopia, members of the Dorze ethnic community sing and dance before, during and after funerary rites in communal ceremonies meant to defeat death and avenge the deceased.

In not too distant Tanzania, the burial traditions of the Nyakyusa people initially focus on wailing but then include feasts. They also require that participants dance and flirt at the funeral, confronting death with an affirmation of life.

Similar assertions of life in the midst of death are expressed in the example of the traditional Irish “merry wake,” a mixture of mourning and celebration that honors the deceased. The African-American “jazz funeral” processions in New Orleans also combine sadness and festivity, as the solemn parade for the deceased transforms into dance, music and a party-like atmosphere.

These lively funerals are expressions of sorrow and laughter, communal catharsis and commemoration that honor the life of the departed.

A way to deal with grief

Grief and celebration seem like strange bedfellows at first glance, but both are emotions that overflow. The ritual practices that surround death and mourning as rites of passage help individuals and their communities make sense of loss through a renewed focus on continuity.

By doing things in a culturally defined way – by performing the same acts as ancestors have done – ritual participants engage in venerated traditions to connect with something enduring and eternal. Rituals make boundaries between life and death, the sacred and the profane, memory and experience, permeable. The dead seem less far away and less forgotten. Death itself becomes more natural and familiar.

Funerary festivities such as Day of the Dead create space for this type of contemplation. As we reminisce over our own losses, that is something we could consider.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Time to Have the Talk! Sex and the Cancer Patient

By Roxanne Nelson, BSN, RN

“So how is your sex life?”

That is a question that a great many cancer patients would love to hear from their oncologists, but unfortunately, sexuality is not a topic that gets much attention.

A panel of experts here at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (PCOS) 2017 tackled the subject of sex and the cancer patient and presented preliminary data demonstrating how “low-tech” interventions can make a dramatic difference for patients.

Sexuality is a somewhat taboo topic in oncology care, and perhaps even moreso in palliative care, explained panel member Anne Katz, PhD, RN, certified sexuality counselor at Cancer Care Manitoba, Canada. “But we know that this is important to patients and their partners across the cancer journey.”

She cited a study (Psychooncology. 2011;21:594-601) that found that fewer than half (45%) of all cancer patients had a conversation with their healthcare provider about sex. By cancer type, 21% of lung cancer patients had such a conversation, as did 33% of breast cancer patients, 41% of colorectal cancer patients, and 80% of prostate cancer patients.

Men, it seems, get the “sex talk” a lot more frequently than women do.

According to Dr Katz, the “whole thing is skewed” by prostate cancer. More than twice as many men speak to their providers about sex as compared to women.

“If we didn’t talk about nausea, if we didn’t talk about constipation, we would be regarded as negligent, even indulging in malpractice,” Dr Katz pointed out. “Yet we are leaving out conversations about this very important quality-of-life issue, which persists into end-of-life care.

“Sexuality is much more than just intercourse. It is about touch and intimacy and about much more than what we do in the bedroom,” she said.

A recent study (J Cancer Surviv. 2017 Apr;11:175-188) again showed that a “preponderance” of men (60%) had a discussion about sex with their provider, whereas fewer than half as many women did (28%).

However, healthcare providers thought “they were doing a good job,” with almost 90% reporting that they were. “So there is a very large gap as to who is saying what and who is hearing what,” explained Dr Katz.

Another problem is that the cancer patient is much more likely to raise the topic with their provider, rather than the reverse. This is a problem, she pointed out, “because in every other area, we raise the topic with our patients, indicating that its important. By not opening the door, by not starting the conversation, we are saying to our patients that ‘this is not important and I don’t want to talk about it.’ ”

Panelist Sharon Bober, PhD, founder and director of the Sexual Health Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, agreed with that summation. “We have to expand our perspective on what sexuality is, in the context of serious illness and palliative care. It’s too easy to be reductionist and think about whether some can or cannot have sex – this isn’t what it’s about.”

Sexuality, she noted, is a human experience across the lifespan. It’s a multidimensional experience that involves physiology, behavior, emotion, cognition, and identity.

“What we can take from some of the qualitative and survey work that’s been done to date is that expressions of sexuality can be a vital aspect of providing comfort and relieving suffering, maintaining connections in the face of life-limiting illness, and affirming a sense of self when other roles are lost,” Dr Bober explained. “When sexually is not made part of care, there is an implicit message that is it no longer important and/or the challenges cannot be addressed.”

Unfortunately, providers often took a medicalized approach, as was evidenced in one study (Contemp Nurse. 2007 Dec;27:49-60). Patient sexuality and intimacy were largely medicalized; the discussion remained at the level of patient fertility, contraception, and erectile or menopausal status, Dr Katz noted.

“There is a lot of active avoidance,” she said. She pointed out that the “patient reports the topic and the oncologist takes three steps back and flies out the door.”

Some of the reasons given for not discussing sexuality were reactions of colleagues, fear of litigation, and fear of misinterpretation.

The topic needs to be brought up in the context of quality of life, she emphasized, “but we need to open the door.”

There is the fear of not knowing what to say, but there is “Dr Google, there are books, there are experts, and if you don’t know, you will find the resources to refer patients to them,” Dr Katz said. “We have a responsibility to discuss sexual side effects of cancer treatment.”

Very Brief but Very Effective

Sexual function is profoundly disrupted by gynecologic cancer treatment, and 90% of patients with ovarian cancer report distressing changes in sexual function. “The good news is that ovarian cancer patients are living longer, and almost 50% of survivors will live many years post diagnosis,” explained Dr Bober. “But they often have to endure multiple surgeries and multiple rounds of chemotherapy, and sexuality and distress are generally not addressed.”

She pointed out that with ovarian cancer patients, “no one talks about this. The thought Is often that you have bigger fish to fry, you may not live anyway ― there are all kinds of reasons that this doesn’t get addressed.”

Dr Bober described an intervention that they devised at Dana Faber to address sexual dysfunction in ovarian cancer survivors. Not only was it brief, easily accessible, and “doable” by patients, but final results showed that it was quite effective.

The format was integrative. It was composed of a single half-day group intervention with a didactic teaching and experiential exercises, coupled with an individualized action plan. After the session was completed, the participants were asked to reflect on what was pertinent to them and what they were going to work on during the next 6 weeks.

The session was followed by a brief telephone call, in which the action plan was reviewed and additional support was offered if needed, to uncover additional challenges that needed to be addressed.

Because this was a pilot study, it did not include a control group per se, Dr Bober explained, but participants served as their own controls. This was accomplished by having a 2-month run-in period, during which women filled out surveys at baseline then waited for 2 months before completing the survey a second time before beginning the intervention. The purpose of the 2-month run-in period was to estimate changes in symptoms that could not be attributed to the intervention.

The design comprised three modules. Module 1 was targeted on sexual health education, which discussed vaginal health, enhancing arousal, and increasing low desire. Module 2 involved body awareness and relaxation training, in which participants learned pelvic floor education, progressive muscle relaxation, and body scan. Module 3 involved a mindfulness-based cognitive training, which sought to increase nonjudging awareness of automatic thoughts, with progression from avoidance/distraction to acceptance.

The cohort included 46 women with stage I-IV ovarian cancer who reported at least one distressing sexual symptom. The mean time since diagnosis was 6.3 years (range, 1 – 20 years). “Twenty years is a very long time to be dealing with distressing sexual problems,” emphasized Dr Bober.

Within this group, 13% were currently receiving chemotherapy, and 44% were currently taking medication for anxiety, depression, or pain.

In evaluating the program, 97% of the women found the it helpful, 100% found it easy to understand, and 95% found the it enjoyable.

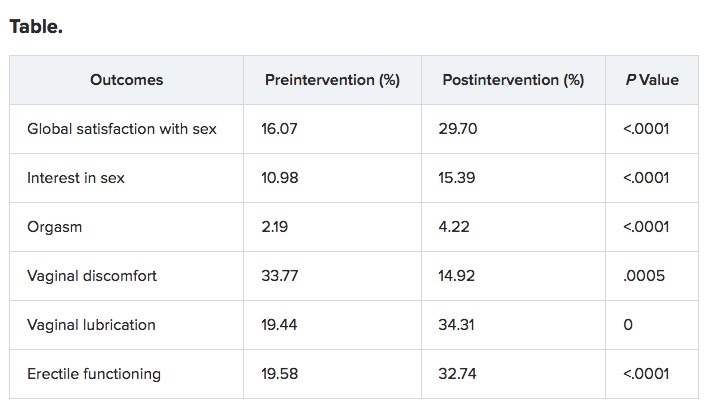

With regard to helping sexual functioning, “There were no changes during the run-in period, for the most part, demonstrating that time alone did not change the situation,” said Dr Bober. “But at month 2 after the interactions, there was significant improvement over multiple domains of sexual function. And for the most part it held over to 6 months.”

Although the pilot study was not focused on mental health per se, there was significantly less psychological distress observed in the participants, especially regarding symptoms of depression and distress.

It was a small pilot study, she emphasized, but the implications are that brief sexual health rehabilitation in the context of serious illness is effective. “There was meaningful improvement in sexual function and emotional distress, and improvements at 6 months.”

Dr Bober emphasized that there is an enormous need for evidence-based intervention research, with interventions conducted outside of an academic center in order to reach more people. “There is a need for identify optimal methods for delivery,” she said. “In some of the palliative care literature, patients talk about struggling with this issue within 2 to 3 months before they die, so this is not something that is relevant only if you’re well.”

Pilot Study in Transplant Patients

Similar to other oncology settings, sexual dysfunction is a common long-term complication for survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT), but it is rarely discussed, and interventions to enhance sexual function in this population are lacking.

The preliminary efficacy of a multimodal intervention designed to improve sexual function in allogeneic HCT survivors was very encouraging, reported Areej El-Jawahri, MD, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivorship Program at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues conducted a pilot study to assess the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the intervention in a cohort of 50 patients. The participants were at least 3 months’ post transplant and had screened positive for distress caused by sexual dysfunction.

“There was a very wide age range, from 24 years to 75 years,” she said. “The median time from HCT at enrollment was 29 months, but there was also a wide range between 3 and 173 months.”

The primary endpoint of the study was feasibility: 75% of patients who screened positive would agree to participate and attend the first visit, and at least 80% would attend at least two intervention visits.

The majority of patients had acute leukemia (55%), and nearly 64% had chronic graft vs host disease (GVHD).

The format consisted of monthly intervention visits with trained study clinicians. The visits focused on assessing sexual dysfunction, educating and empowering patients to address this topic, and implementing therapeutic interventions that targeted their specific needs.

The PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measure, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) were used to assess sexual function, quality of life (QOL), and mood at baseline and 6 months post intervention.

The study met its primary endpoint of feasibility; 94% (47/50) agreed to participate, and 100% of this group attended at least two interventions. The median number of visits were two (range, two to five). The median duration of the first visit was 50 min; for the second visit, it was 30 min. In addition, 28% (13/47) had a partner attend an intervention visit.

Results were encouraging, Dr El-Jawahri pointed out. “Sexual activity in the group increased.”

Before the intervention, 32.6% of patients reported not engaging in any sexual activity; that number declined to 6.5% after the intervention.

In men, the following therapies were implemented: phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDI) on demand (57%), psychoeducation (52%), penile constriction rings (48%), referral to a sexual health clinic (9%), daily PDI treatment (4%), topical GVHD treatment (4%), and hormone replacement therapy (4%).

For women, therapies included vaginal estrogen (67%), dilator (63%), lubricant (58%), psychoeducation (42%), topical GVHD treatment (42%), topical lidocaine (8%), and referral to a sexual health clinic (4%).

“All outcomes were clinically and statistically significant,” said Dr El-Jawahri.

The program was efficacious in improving QOL and mood.

“This has very promising efficacy, but we need to conduct a randomized clinical trial, and there is a need to asses longer-term outcomes,” Dr El-Jawahri concluded. “It also has potential for adaptation to other types of cancer survivors as clinicians to deliver this kind of intervention and allow for dissemination.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How to Help Your Kids Cope With the Loss of the Family Pet

[P]ets are part of the family, so it makes sense that losing one is tough on everyone, including our children. A pet’s death may be the first time they’ve ever experienced a real loss, and as a parent, it can be difficult to know how to start a conversation about life, death, and grieving in a way they can understand, but that won’t heighten their sadness.

Last week, we put our 12-year-old dog to sleep five weeks after he was diagnosed with lymphoma. It was a brief but rapidly debilitating illness, and I wondered if my kids would understand that a dog who was quite healthy only two months ago was now gone. Surprisingly, they took it much better than I did. My 3-year-old gave me a hug, then told me, “I don’t know why you’re crying, Mom. Gus was sick, and now he’s in heaven with grandma’s dog. He’s not sad he died. He’s still happy.”

After briefly wondering if my child was a pet psychic, I realized that his logic was pretty sound. While my son would miss our dog, he knew our pup had been suffering, and he was prepared for the death. He had processed the loss faster and more easily than I did precisely because he was a kid. If you’re dealing with the loss of a family pet, here’s how to help your children process their feelings.

- Make sure your child understands what death means. Gently make sure that your child understands that their pet’s death means the animal will never be physically present again. Don’t be alarmed if it takes awhile — even years depending on their age — for your child to understand that means that your pet can no longer breathe, feel, or ever be alive again. If the death was sudden or unexpected, explaining why or how your pet died might be important to help your child understand the permanence of the loss. Of course, consider your child’s age and ability to understand and only give them developmentally appropriate information.

- Be honest. Telling your child about the death openly and truthfully lets your child know that it’s not bad to talk about death or sad feelings, an important lesson as they will have to process many other losses throughout their lives.

- Follow your child’s lead. Sometimes children are better than adults at accepting loss, especially when they’ve known for some time that their pet had a limited life span or was ill. Don’t attempt to make your child’s grief mirror your own, but do validate any emotions that come up as your child goes through the mourning process, and be ready to talk when they have questions. Age-appropriate books like Sally Goes to Heaven and I’ll Always Love You can also help with communication.

- Don’t be surprised if your child grieves in doses. Children often spend a little time grieving, then return to playing or another distraction. This normal, necessary behavior prevents them from becoming overwhelmed and makes the early days of grief more bearable for them.

- Say a formal goodbye. Consider having a small memorial service where you can all say goodbye, discuss favorite memories, and thank your pet for being part of the family, even if the service is just in your backyard or around the kitchen table.

- Find a way to memorialize your pet appropriately. We often don’t realize how constant our pets were in our lives until they’re gone. By making a photo album, turning a collar into a Christmas ornament, or commissioning personalized art work through Etsy, your whole family will have a positive remembrance of your beloved pet for a lifetime.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!