BY VANESSA HOUK

The hardest steps I ever took happened 17 years ago, on a hot Thursday afternoon in early September, as I walked away from my son’s grave for the first time. The cemetery smelled of juniper and baked dirt, and as my husband Jason and I stood arm-in-arm, readying ourselves to go, I felt the heat rise up from our ankles. I remember how my body slowly lurched forward as we steered each other toward the car while the hot sun filled the high desert cemetery with light. The wind, an almost constant presence out there, was still as I made my way along, feet dodging big clumps of cheatgrass along the way.

Just two days earlier, we’d sat huddled together at the mortuary, “making arrangements” as they called it, which really meant having to tell someone else about how our lives seemingly and without warning came to a halt as Dylan’s heart stopped beating in utero, a week past his due date. He was stillborn. We’d walked out of the hospital carrying a small purple memory box rather than our 10-pound son.

The day we buried Dylan, there were reminders all around me of how the forces of nature could alter everything. Close to the cemetery, outside our then-home of Bend, Oregon, the elevated peaks of Three Sisters weren’t the gentle fairy tale their name suggested, but the result of plates that had shifted deep in the earth, during a process called subduction. Layers of crust had crashed into each other in a fiery show, perhaps tens of thousands of years ago, creating the widest and longest fault lines in the earth.

Subduction zones are places where great trauma lies. And here I was, all these years after the mountains formed, standing in their shadows in the middle of my own destruction. Enveloped in grief. Loss all around me.

***

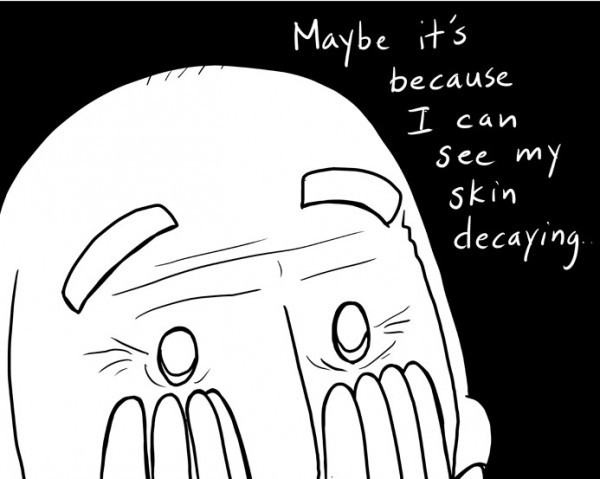

Dylan’s in every step I take as I walk away from his grave. He’s all I can think about as I recall the sound that came out of me when I held him for the first time, “Oh!” His still warm body is wrapped in a white cotton blanket and he is wearing a little white onesie with colorful baby-sized hand prints across it. At first glance, his face looks reddish, and I can see that it’s turning blue, but I am not seeing what he is right now. My eyes are soaking up what he should have been. I can see the slight curve of his nose and the shock of dark hair on his head. His eyes are closed, but I know the sky-blue they would otherwise be. He feels light in my arms as I hold him close against my own skin, and as I study him, I am quiet for a while. He’s brand new and so familiar at the same time.

Perhaps there are still other people in the room, or maybe not. Everything and everyone else recedes and all I see is the top of his head and all I hear are words that come pouring out of some deep recess: “I love you so very much. All the way to the moon and back and around the world three hundred and sixty seven times.”

“He’s brand new and so familiar at the same time.”

Some words I say out loud, and some words I don’t need to give voice to. I know that he hears them. It is an ancient wisdom. I tell him about his family and about his sister. I tell him about his room and our cats. I tell him that we all love him. All this time, I am holding my son for the only time we will be together on this big blue planet. I know that this is something I will never get back. I know I have to remember this fiercely. It will all be over far too soon.

Later, when I can reflect on the funeral, I remember our family and friends dropping what they’re doing to stand with us. I remember our daughter sitting on the ground with friends, and their three little heads bowed together while playing with dolls. I remember visually gathering some of their innocence, and it feeling like something close to hope.

As we drive along the dirt road that leads out of the cemetery, I slump down in the seat. By the time we reach the fence, as it will happen every single time, perhaps for the rest of my life, my tears water the desert air. Even as the miles pass and we make our way back to Bend, toward our families and the small gathering at his grandparents’ house, inside my head, I stay in the cemetary where my son is buried, my heart turned inside out.

***

After Dylan’s funeral, we walked back to our apartment and into a life that the three of us no longer fit into. For more than a year, we did our best to go through the motions—we worked, we took short family vacations to the coast and southern Oregon, and we tried to dodge the grief that followed us. Then one day, our 4-year-old daughter asked, “Mom, we used to be so happy, huh?” I nodded. “And then Dylan died and now we’re all so sad.” Six words leapt at me. “When will we be happy again?”

Up until her brother’s death, our lives had been full of quiet walks down a gravel-filled road on the outskirts of Sunriver, where we scouted ospreys, baby hawks, and porcupines. “Look,” I’d say while pointing out some amazing new discovery as we wandered the edge of the Deschutes River. We lived in a sweet log cabin that Jason’s Aunt Jennifer built with her own hands. At night there was a gathering of stars above us as the clearest moon lit up the sky. It was by all accounts an idyllic life and for her, it was a gentle childhood surrounded by a forest of towering but friendly ponderosas and jack pines.

Now I felt like we’d all been catapulted headfirst into the kind of neighborhood you didn’t want to be in after dark. We’d never been here before, didn’t know where we were going, and from what I could see, there weren’t any road maps. Clearly we’d lost our bearings. How could we go from such a well-crafted “before” to such an unimaginable “after”?

“How could we go from such a well-crafted ‘before’ to such an unimaginable ‘after’?”

That fall, my daughter could have entered pre-school, but the thought of sending her away, even just for a few hours, was inconceivable to me. She was my reason for getting up and facing each day. When I wanted to hole up and stay home, she would cajole me to take her to the park so she could swing higher and higher. She pointed to birds and flowers around our neighborhood and made me see beauty again. “Look at that!” she would say. And on the days when I could barely drag myself out of bed in the morning, she would be there. “I love you,” she would remind me. All those lessons I had poured into her, came right back to me when I needed them most.

And all the time, those six words pulled me along, inspiring me to keep trying to find something that resembled happiness in this new form. We moved back to southern Oregon and eventually made our way back to Ashland, where bright red flags lined Main Street and the lush foothills around us offered a sense of peace. I didn’t know it back then, but we were charting our own map, however imperfect. We threw ourselves into volunteer work, discovering in the process that fighting for the rights of low-income people—for better access to health care, economic justice, and independent media that tells the stories behind the issues—felt especially fortifying. We rooted ourselves in southern Oregon until it felt like home. Healing crept up on us, not all at once, but in tiny flashes of kindness. Two more daughters were born and grew.

Above us, the moon kept rising and lighting up the darkness. Seventeen years passed.

***

Here’s the thing that nobody else will tell you about grief. Sometimes, however uncomfortable it is, you just have to sit with sadness for awhile. Sorrow waxes and wanes. You can ground yourself in simple things while time drags along; I recommend the taste of a fresh, ripe peach, listening to the sounds that a hummingbird’s wings make when they visit the feeders, and love notes penned to a small daughter, perhaps added into a brown paper lunch bag with a funny little drawing on one side.

“Sometimes, however uncomfortable it is, you just have to sit with sadness for awhile.”

The sorrow that most of us want to flee helps spit-shine the lens, until we see things more clearly, feel things more deeply. And perhaps, in its wake, grief may even beget a baffling richness.

Complete Article HERE!