By SUE MANNING

For those who are dying, it’s clear why all dogs go to heaven.

They provide comfort not just in death, but in other difficult times, whether it’s depression, job loss or a move across country. Dogs know when people are dying or grieving through body language cues, smells only they can detect and other ways not yet known, experts say.

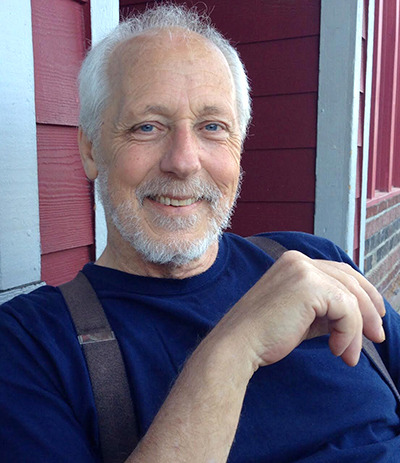

As a hospice veterinarian, Jessica Vogelsang knows how much “being there” can mean to struggling people or pets. She’s director of Paws Into Grace in Southern California, a group of vets who provide end-of-life care and euthanasia for pets at home.

The San Diego vet finished her first book, “All Dogs Go to Kevin: Everything Three Dogs Taught Me (That I Didn’t Learn in Veterinary School),” just before learning her mom, Patricia Marzec, had an inoperable brain tumor. The title of the memoir published last month refers to what Vogelsang’s toddler heard when he was told all dogs go to heaven.

Her parents moved in so Marzec could enjoy her last months with family, and Vogelsang’s golden retriever, Brody, picked up on the changes. He always jumped on her parents but stopped when they arrived in April.

“He knew Mom was sick. He was with her 24-7,” Vogelsang said. “He was trying not to be too obvious, but Dad was on one side and he was on the other.”

Brody would lay by Marzec’s feet or rest his head on her lap when he sensed she was sad. He wedged in next to her when hospice workers came by, ignoring her shaking hand as she patted his head, Vogelsang said.

“He is still my dog, but he knew when they came they needed him more than I did,” she said.

Dogs know to comfort people by sniffing out some cancers, such as on the breath of a lung cancer patient, said Dr. Bonnie Beaver, professor at Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and executive director of the American College of Veterinary Behaviorists.

But most often, it’s about body language.

“They recognize fragile, slumped over, not moving as well,” Beaver said. “That’s how they read each other. … They are great at it, and we are not.”

Some rest homes and hospices that have live-in dogs to comfort patients even use a dog’s behavior — such as who the animal chooses to sleep with — as a sign to tell relatives to come say their goodbyes.

“A lot of resident dogs know those people and know something is different, whether the smell changes or they are moving less,” Beaver said.

Dogs also can help those dealing with other challenges.

In the book, Vogelsang introduces pets that got her through some life changes. As a little girl, her Lhasa Apso named Taffy helped her adjust to an unwanted move from New England to California.

Just after the birth of her first child, her golden retriever Emmett wouldn’t leave her alone as she struggled with postpartum depression and a new career as a veterinarian. He gave her love, as well as looks that led to some soul-searching to get the help she needed, Vogelsang said.

Later, an older Labrador retriever named Kekoa taught her to let go of unrealistic expectations as she balanced career and motherhood. When the dog got cancer, Vogelsang didn’t push endless procedures and medications, because it wasn’t right for Kekoa. That led her into the hospice-care field.

After Vogelsang’s mother moved in, the family spent two months watching movies, eating cookies and watching butterflies flit across the yard. Pat Marzec even read her daughter’s book, giving her approval.

She died June 3, about a month before it went to print.

“Those last two months we had were just an incredible time,” Vogelsang said. “Death is just a moment. Life is everything else leading up to it.”

Complete Article HERE!